SALA CLIII

IL PROCESSO DI ROMANIZZAZIONE

Dalla seconda metà del IV sec. a.C., con le guerre sannitiche, ebbe inizio il processo di espansione che portò Roma alla conquista della egemonia in Italia e nel Mediterraneo, un processo che ebbe come conseguenza la progressiva romanizzazione - cioè l’integrazione nella realtà unitaria dell’impero - delle comunità e dei popoli alleati e sottoposti. Roma utilizzò vari mezzi per esercitare l’egemonia: l’incorporazione nel proprio territorio di altre città (municipia), la fondazione di colonie, la concessione della cittadinanza senza diritto di voto (civitas sine suffragio), trattati bilaterali (foedera). Le comunità dell’impero erano, per lo più, subordinate a Roma in politica estera ed erano tenute a fornirle contingenti militari; tuttavia godevano di una certa autonomia negli affari interni. Nonostante le ingerenze di Roma nella vita delle comunità soprattutto dal II sec. a.C., la romanizzazione fu anche un fenomeno spontaneo, perché le comunità erano in buona misura compartecipi dei benefici derivanti dall’egemonia di Roma nel Mediterraneo, e soprattutto le élites locali desideravano prendere parte alla gestione dell’impero. La romanizzazione fu un fenomeno estremamente complesso ed estremamente diversificato nei suoi esiti locali. I testi esposti in questa sala, provenienti dall’Italia meridionale e da Roma, ne danno solo uno spaccato, per quanto significativo. Sono segni di romanizzazione la diffusione della lingua latina, l’uniformità dello schema delle magistrature cittadine e degli statuti municipali nelle realtà locali (nn. 1, 5-6) l’adozione da parte loro delle leggi e del diritto romani; ma anche le leggi con cui Roma regolava la procedura penale (nn. 3, 5), il regime delle terre demaniali (n. 3), i rapporti con singole comunità (n. 4), o cercava di rendere più efficiente l’amministrazione dell’impero (n. 2).

The process of Romanization

From the Samnite wars on (second half of the 4th century BC), Rome went through a great process of expansion, gaining military, political and economic hegemony over the rest of Italy and in the Mediterranean. This process resulted in a gradual Romanization - i.e. integration into the Empire - of the allied or subject populations. To exercise its hegemony, Rome availed itself of various means, such as the incorporation into its territory of other cities (municipia), the foundation of colonies, the concession of citizenship without the right to vote (civitas sine suffragio) and the concluding of bilateral treaties (foedera). The allied communities were, for the most part, subjected to Rome in their foreign policy, and were under the obligation to provide it with troops. They enjoyed, however, a certain degree of autonomy in their internal affairs. Although, especially from the 2nd century BC, the government of Rome often interfered heavily into the life of the individual communities, Romanization also took the form of a spontaneous phenomenon, because the allies looked up to the Roman model, benefited from Rome’s hegemony in the Mediterranean and, above all, their local elites wished to take part in the management of the Empire. The Romanization of Italy was by then essentially accomplished on the juridical plane. The epigraphic texts on exhibits in this room, most of which are from southern Italy, illustrate the different ways in which Rome managed its empire in the Republican age. They include judicial laws and municipal statutes (nos. 1, 5-6) and others illustrating the internal management of public administration in “Romanized” communities (nos. 3, 5) or providing examples of how Rome managed its relations with its overseas allies (no.3). The remaining epigraphs on exhibit also concern important aspects of the social life of Roman Italy.

Le città romane dell’Italia meridionale

Prima della guerra sociale (91-89 a.C.) le città dell’Italia antica avevano, in relazione a Roma, diverse condizioni giuridiche. Alcune rientravano nell’ager manus e godevano della cittadinanza romana, come i municipia. - città preesistenti alla loro incorporazione nello stato romano- e le coloniae civium Romanorum: presidi militari composti da un piccolo nucleo di cittadini di pieno diritto (in genere 300) inviati da Roma. Altre città erano stati formalmente indipendenti, come le colonie di diritto latino (coloniae Latinae) e le civitates foederatae, legate a Roma da un trattato. Queste ultime potevano avere varia origine etnica (greca, etrusca, osca, etc.). Le città erano il perno della romanizzazione e dell’organizzazione amministrativa romana, ma in alcune regioni della penisola il fenomeno urbano era poco diffuso ed il territorio era strutturato in distretti territoriali (pagi) al cui interno sorgevano piccoli nuclei abitativi (vici). Dopo la guerra sociale e la concessione della cittadinanza romana alle popolazioni della penisola, bisognò riorganizzare le strutture amministrative delle comunità locali per consentire un’adeguata partecipazione alla vita politica dello stato romano. Si ebbe così l’estensione dell’istituto del municipium alle colonie latine e agli alleati. Lo schema dell’ordinamento municipale era uniforme: i quattuorviri erano i magistrati supremi con poteri giurisdizionali, c’era poi il consiglio degli ex magistrati (i decurioni), e l’assemblea popolare. Gli statuti municipali (nn. 1, 5-6) derivavano da un archetipo comune, adattabile alle esigenze locali.

The Roman Cities of Southern Italy

Before the Social War (91-89 BC), the relations between the cities of ancient Italy and Rome were regulated by different juridical status. Some cities were part of the ager Romanus and enjoyed Roman citizenship, e.g. the municipia - townships pre-existing their incorporation into the Roman state - and the colonies of Roman citizens (coloniae civium Romanorum). Others were formally independent states, e.g. the colonies ot Latin law (coloniae Latinae) and the civitates foederatae - i.e. bound to Rome by a treaty - which had different ethnic origins (Greek, Etruscan, Oscan etc.). The cities were the core of the process of Romanization and of the Roman administrative organization. In some regions of the peninsula, however, urbanization was scarce, and their territories were hence divided into territorial districts (pagi) in which there were small settlements called vici. After the Social War and the concession of Roman citizenship to all the populations of the peninsula, it was necessary to reorganize the administrative structures of the local communities to grant them an adequate participation in the political life of the Roman state. The statute of municipium was thus extended to the Latin colonies and to the allies. The pattern of the municipal organization was uniform: it was made up of the quattuorviri, the supreme magistrates, with jurisdictional powers, the council of former magistrates (the decurions), and the popular assembly. Municipal statutes (nos. 1, 5-6) were based on a common archetype, for reasons of uniformity, but could be adjusted to local necessities.

La Misurazione della terra

Nel 133 a.C. il tribuno della plebe Tiberio Gracco per far fronte all’occupazione abusiva e alla concentrazione in poche mani dell’ager publicus (i terreni demaniali), presentò una proposta di riforma agraria. Essa prevedeva di limitare il possesso di ager publicus per ogni individuo a 500 iugeri (125 ettari), più 250 iugeri per ciascun figlio fino a un massimo di 1000 iugeri. All’occupante era garantito il possesso perpetuo di tali quote. I terreni eccedenti ritornavano allo Stato e una commissione di tre membri (Triumviri Agris Dandis Adsignandis) provvedeva a redistribuirli ai nullatenenti in lotti inalienabili. Osteggiata dagli occupanti abusivi delle terre demaniali, la commissione incontrò numerose difficoltà, tra cui, stabilire, in assenza di mappe catastali aggiornate, lo stato giuridico privato o pubblico dei terreni. Una nuova legge le diede, quindi, anche potere giudicante (Triumviri Agris Dandis Iudicandis Adsignandis) e fu avviata una vasta opera di misurazioni catastali che affiancò il recupero dell’agro pubblico e la distribuzione dei lotti.

The land measuring

In 133 BC, Tiberius Gracchus, tribune of the plebs for that year, presented a bill proposing an agrarian reform limiting possession of public land on the part of privates to 500 iugeri (125 hectares), a quota that could be increased by 250 iugeri for each child up to a maximum of 1000 iugeri. Permanent possession of these quotas would be guaranteed to the owner. The surplus land would be incorporated by the State. A triumviral commission Triumviri Agris Dandis Adsignandis), was entrusted with the task of delimiting inalienable plots intended for persons without property. The triumviri were confronted with many obstacles: it was difficult, in absence of updated cadastral maps, to establish if a given plot of land was public or private, and to settle disputes with the Italic allies, whose territories were also involved in the program; furthermore, they had to face the hostility of the rich landowners who had monopolized the use of public land. To cope with all these problems, a new law was passed giving them judicial powers as well (the commission was hence renamed Triumviri Agris Dandis Iudicandis Adsignandis). A large scale operation of cadastral measurement was thus set up, public land was recuperated and the plots were redistributed. A series of “gromatic” (i.e. land-meansuring) cippi found in the Picenum and in Campania, Samnium and Lucania, including the cippus of Atena Lucana (n. 7), document the activities of this agrarian commission in these regions, i.e. the measuring and delimiting of private from public land. Centuriatio was the basic operation: the division of land into a regular grid of horizontal (decumani) and vertical (kardines) axes traced on the ground with a groma.

I Calendari

Il calendario arcaico comprendeva dodici mesi per 355 giorni. Era lunisolare: il succedersi dei mesi era basato sulle lunazioni, ma si colmava ogni due anni la differenza sulla rivoluzione terrestre con un mese intercalare di 22 o 23 giorni. La differenza era dunque colmata per eccesso, per cui talvolta era omessa l’intercalazione. Il compito di registrare le lunazioni e di ordinare le intercalazioni spettava ai pontefici, massima autorità religiosa romana. Il nostro calendario discende dalle riforme di Giulio Cesare (46 a.C.) e di papa Gregorio XIII (1582), fondate sul calcolo astronomico del periodo di rivoluzione terrestre. Il mese romano era diviso in tre parti: calende (abbreviate con Kal o K), none (Non), idi (Eid) che originariamente indicavano tre momenti della lunazione. La funzione delle nostre settimane era svolta dalle nundinae (“nove giorni”). Esse comprendevano in realtà otto giorni, e il loro nome si spiega col conteggio romano che includeva anche il primo giorno della serie successiva. I giorni erano contrassegnati dalle prime otto lettere dell’alfabeto (A-H), dette nundinali. All’inizio di ogni serie si teneva il mercato. Le nundinae saranno sostituite dalla settimana a partire dal I sec. d.C.

I fasti sono i calendari che contengono tutti i giorni dell’anno (nn. 15, 16). I feriali annotano soltanto le feste (n. 18). I Menologi forniscono per ogni mese il numero dei giorni, la loro suddivisione, la lunghezza del giorno e della notte, il segno zodiacale, il nume tutelare, le operazioni agricole, le feste ed i riti più importanti (n. 14). Gli Indices nundinarii sono liste di città con l’indicazione dei giorni in cui vi si svolgevano le nundinae, mercati cittadini che si tenevano ogni otto giorni (n. 17).

Calendars

The archaic calendar comprised 355 days divided into twelve months. It was lunisolar, that is, the succession of months was based on the revolutions of the moon; however, every two years the difference with the solar year was compensated by intercalating a leap-month of 22 or 23 days. The difference was thus actually overcompensated, which is why the intercalation was sometimes omitted. The task of recording moon revolutions and ordering intercalations fell to the pontifices, the highest Roman religious authority. Our own calendar derives from the reforms of Julius Caesar (46 BC) and pope Gregorius XIII (1582), founded on astronomical calculations of the duration of the Earths revolution. The Roman month was divided into three parts: Kalends (abbreviated as Kal or K), Nones (Non), and Ides (Eid). These names originally designated moon phases. The function of our weeks was performed by nundinae. The word means “ninth day”, but they actually comprised only eight days. This is due to the Roman counting system, which also included the day one counted from. The days were designated by the first eight letters of the alphabet (A-H), hence called “nundinal letters”. Markets were held at the beginning of each nundinal cycle. Nundinae were replaced by weeks in the first century AD. Fasti are calendars listing all the days of the year (nos. 15, 16). Ferialia only indicate holidays (no. 18). Menologia give the number of days of each month, their subdivision, the length of day and night, the sign of the zodiac, the tutelary deity, agricultural tasks, and the principal holidays and rites (no. 14). Indices nundinarii are lists of towns with indications of the days when nundinae were held in each. Nundinae were town markets held every eight days (no. 17).

Spazio e tempo

L’ORGANIZZAZIONE E IL CONTROLLO DELLO SPAZIO

L’organizzazione del territorio, nella mentalità romana, deve proiettare nello spazio un duplice ordine: politico-amministrativo, stabilendo la condizione giuridica di ogni porzione di territorio; divino, riproducendo sulla terra l’ordine cosmico, attirando così sulla comunità il consenso degli dei, garanzia di prosperità comune. I cippi di confine erano infissi nel terreno per segnalare la natura e i limiti delle proprietà private e pubbliche nonché delle circoscrizioni territoriali amministrative. L’estrema importanza rivestita da queste operazioni è rivelata dal complesso rituale che presiede alla collocazione dei cippi (nn. 7, 8, 10), dall’importanza del culto di Terminus (confine; pietra di confine), dalla legge del re Numa che dichiarava sacer (sacrilego) chiunque avesse scalzato un segno di confine.

L’ORGANIZZAZIONE E IL CONTROLLO DEL TEMPO

I Romani regolavano accuratamente la scansione del tempo umano, qualificando con precisione i giorni dal doppio punto di vista dell’attività umana e del culto degli dei. La qualità dei giorni era indicati da sigle:

F =fastus, i giorni in cui era lecito amministrare la giustizia. Il termine fasti indica, per estensione, il calendario stesso.

N = nefastus, i giorni in cui non si poteva amministrare la giustizia, inadatti a qualsiasi attività.

NP = contraddistingue quasi tutte le feste pubbliche, ma non ci è stato tramandato il significato. Sono giorni nefasti, ma evidentemente di una qualità speciale. Potrebbe trattarsi di giorni in cui si celebravano i riti espiatori (nefaspiaculum).

C = comitialis, giorni fasti in cui si potevano tenere le assemblee.

EN = endotercisus, giorni (sette in tutto) divisi in tre parti, nefasti nella prima e nella terza parte, fasti in quella mediana. Esistono poi giorni religiosi, in cui è vietata qualsiasi attività cultuale e civile. I giorni festivi per eccellenza sono le feriae. Nel calendario arcaico, precedente la riforma di Giulio Cesare del 46 a.C., esse erano 120 su 355 giorni. Dei 235 giorni fasti, solo 92 erano comitiales, cioè dedicati all’attività politica. Essi aumentarono gradualmente, per il primato riconosciuto agli affari pubblici.

Space and time

the organization and control of space

Territorial organization, as the Romans conceived it, was a spatial projection of political activity, and was a way to manifest the consensus of the gods, indispensable to public prosperity. The roads and border cippi made tangible, and somehow permanent, the collective image of the appropriation and valorization of land. The border cippi were erected to delimit and indicate public and private property, as well as administrative territorial districts. The extreme importance originally attributed to these operations is borne out by the elaborate ritual followed in the erection of the cippi (nos. 7, 8,10), the importance of the cult of Terminus and Numas law branding as sacer whoever removed a boundary stone. The cippi placed to delimit the ager publicus according to the Gracchan laws are of great historical interest. Some examples are on exhibit on the other side of the room.

the organization and control of time

The Romans accurately fixed the subdivisions of time regulating the activities of the city. They classified the days from the double point of view of human activity and the cult of the gods. The acronyms indicating the characteristics of the days are the following:

F: faustus: on fasti days it was licit to administer justice. The ter fasti eventually was used to indicate the calendar itself.

N: nefastus: on these days, one could not administer justice or engage in any other kind of activity.

NP: the meaning of this acronym is not known. It is used for nearly all public festivals. On these days, all profane activities were suspended and they were therefore nefasti, but obviously special.

C: comitialis, the fasti days on which it was licit to hold the comitia.

EN: (endotercisus), days divided into, three parts, nefasti in the first and third part, fasti in the middle one (there were seven of them in all).

There also existed a certain number of days qualified as “religious”, on which any profane, religious or public activity was interdected. The festive days par excellence were the feriae. In the pre-Julian calendar there were 120 of them, out of 355 days. They generally occurred on odd days, so as to avoid the taking place consecutively. Of their the approximately 235 days indicated as fasti, only 92, called comitial days, were devoted to political activity. These were gradually increased on account of the growing importance attributed to political affairs.

Clicca sulle immagini per vedere l'ingrandimento.

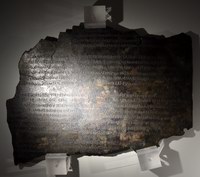

Tavola di Eraclea 1

Calco in gesso da Eraclea - Inv. 2481 (CIL I2, 593) Calco della taccia posteriore di una delle due Tavole di Eraclea esposte nella prima sala, riutilizzata nel I secolo a.C. per incidervi l’ultima parte di un complesso testo legislativo in lingua latina, in un periodo successivo alla guerra sociale e all’incorporazione come municipium della città greca di Eraclea nello stato romano. Nel testo superstite sono presenti alcune norme che riguardano l’organizzazione interna di Roma: esclusione di una categoria di persone dalle distribuzioni di frumento, disposizioni sulla manutenzione delle vie pubbliche urbane e suburbane, regolamentazione del traffico dei carri e dell’utilizzazione degli spazi e degli edifici pubblici. Le altre norme stabiliscono i casi di ineleggibilità alle cariche municipali, dispongono che le operazioni di censimento delle singole comunità d’Italia siano effettuate in concomitanza con quelle di Roma e che una copia dei documenti relativi venga custodita negli archivi pubblici di Roma; si statuisce, infine, che il commissario romano inviato in un municipium fundanum (categoria di comunità di discussa identificazione) ad apprestare lo statuto, abbia un anno di tempo per correggere o integrare lo statuto tenendo conto delle nuove disposizioni. A lungo si è pensato che l’iscrizione latina riproducesse una generale e unitaria sistemazione (lex Iulia municipalis) data da Cesare, negli anni della sua dittatura, alla vita amministrativa delle comunità di cittadini romani. Ma il fatto di trovare associate, in un unico testo, norme che riguardano l’organizzazione interna di Roma, e altre che concernono la vita politico-amministrativa delle città romane, fa pensare che il documento sia piuttosto un insieme composito di parti di leggi romane, votate tra l’età sillana e l’età cesariana, senza che si possa determinare con certezza la natura di una simile “raccolta” di norme e da quale autorità la loro pubblicazione promani: se cioè dagli stessi magistrati locali di Eraclea o dall’autorità centrale a Roma.

Tables from Heraclea

Mould of Heraclea - Inv. 2481 (CIL I2, 593) - Cast of the back face of one of the two tables from Heraclea on exhibit in the first room was reused - in a period following the Social War and the incorporation of the Greek city of Heraclea into the Roman state with the status of a municipium - for the engraving of the last part of an elaborate legislative text in Latin. This remaining part of the text contains norms concerning the internal organization of Rome: the exclusion of a certain category of people from the distribution of wheat, measures for the maintenance of the urban and suburban public roads, regulation of carriage traffic and of the use of public buildings and areas. The other norms prescribe the cases of ineligibility to municipal offices, establish that the census of each Italian community must be carried out at the same time as the Roman one, and that a copy of the documents of the census must be deposited in Rome’s public archives; finally, they give every Roman commissioner sent to a municipium fundanum (a category of communities the exact nature of which is debated) to prepare its statute a year’s time to correct or integrate it according to these new norms. This Latin inscription has long been thought to reproduce a general legislative regulation of the administrative life of the communies of Roman citizens imposed by Caesar during his dictatorship. However, the association, in a single text, of norms concerning the internal organization of Rome and others that regard the political and administrative life of Roman cities seems rather to suggest that the text itself is a heterogeneous assemblage of passages of different Roman laws, voted between the time of Silla and that of Caesar. The nature of this collection of norms is dubious. It is also uncertain which authority issued it, the local magistrates of Heraclea themselves or the Roman central government.

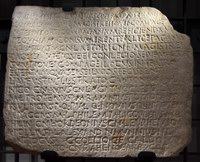

2 Lex Antonia de Termessibus

Bronzo - I secolo a.C. - Roma, già Collezione Farnese. - Inv. 2638 (CIL I2, 589)

La tavola fu trovata insieme alla lex Cornelia de XX quaestoribus nel XVI secolo a Roma, nelle rovine del Tempio di Saturno, ai piedi del Campidoglio. In alto a sinistra la numerazione della tavola: “I de Termesi(bus) Pisid(is) mai(oribus)”. Sono visibili i fori dei chiodi per l’affissione e interventi di restauro. La tavola di bronzo contiene la parte iniziale della legge, databile probabilmente al 68 a.C., che regolamentava i rapporti tra Roma e gli abitanti di Termessus maior, città della Pisidia, regione dell’Asia minore. Nel testo si ripristina la autonomia di Termessus, sancita da una precedente norma risalente al 91 a.C., alla quale la legge fa più volte riferimento. La tavola contiene i primi sei capitoli della legge e parte del settimo; riguardano la libertà dei cittadini, l’autonomia, la proprietà del territorio, di altri beni pubblici e privati, anche in relazione alla guerra mitridatica; si regolamentano i rapporti giuridici tra gli abitanti di Termesso e i cittadini romani e la riscossione dei diritti doganali. Di insostituibile valore documentario per la storia di Termesso nel I secolo a.C., la lex Antonia testimonia, su di un piano più generale della ben nota duttilità della politica romana nei confronti delle città e della loro indispensabile funzione di raccordo tra il centro e le disperse realtù locali, all’interno dell’organismo imperiale mediterraneo.

2 Lex Antonia de Termessibus

Bronze – 1st century BC. - Rome, formerly in the Farnese collection - Inv. 2638 (CIL I2, 589). - Found together with the Lex Cornelia de XX quaestoribus in the XVI century in Rome, among the ruins of the Temple of Saturn, at the foot of the Capitol. At the top, on the left, is the numbering of the table: “I de Termesi(bus) Pisid(is) mai(oribus)”. The table presents holes for its affixing and restorations. The text is the first part of a law, probably dated to the year 68 BC, regulating the relations between Rome and the inhabitants of Termessus maior, a city in Pisidia (a region of Asia Minor).This law reaffirms the autonomy of Termessus, which had already been proclaimed in an earlier document going back to 91 BC, often referred to in the text.The table contains the first six chapters of the law and part of the seventh. They deal with the liberty of the citizens, the autonomy of the city, the property of its territory, the property of other public and private wealth, also with regard to the consequences of the mithridatic wars. They also regulate the juridical relations between the inhabitants of Termessus and Roman citizens, and the exaction of duties. The Lex Antonia is an exceptional document of the history of Termessus in the 1st century BC. It bears witness to the well-known ductility of Rome’s politics toward the cities of its empire, and to its indispensable role of mediating between the dispersed local communities of the Mediterranean and the center.

3 Tavola Bembina

frammenti di lastra in bronzo inv. 2636-112521 (CIL I2, 583 e 585). - La cosiddetta Tabula Bembina è una lastra bronzea frammentaria, iscritta sui due i lati, scoperta tra la fine del Quattrocento e gli inizi del Cinquecento in località imprecisata. Una piccola porzione fu rinvenuta negli anni Settanta del XIX sec., probabilmente presso Fossombrone nelle Marche. Il nucleo principale era appartenuto ai duchi di Urbino. All’inizio del XVI sec. entrò in possesso dell’umanista Pietro Bembo, da cui il nome. Confluì poi nella collezione Farnese, ereditata nel Settecento da Carlo di Borbone e trasferita a Napoli. Ci sono pervenuti dodici frammenti; otto sono conservati nel Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli. I testi si datano alla fine del II sec. a.C. Il più antico, è parte di una legge giudiziaria sulle procedure dei processi per le malversazioni dei magistrati romani. Sull’altro lato fu incisa successivamente una legge agraria che regolava il possesso delle terre demaniali in Italia e nelle province di Africa e Grecia.

3 Tabula Bembina

fragments of a bronze plate inv. 2636-112521 (CIL I2, 583 e 585). - In the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli are kept eight of the twelve fragments of the “Tabula Bembina”, so called because it belonged to the humanist Pietro Bembo. These fragments are the remains of a bronze slab on the two faces of which were engraved the texts of two Roman laws. On the main face was a judicial law prescribing the procedures to be followed in trials for crimes of concussion perpetrated by Roman magistrates (lex de repetundis). The slab was later reused to engrave a law of the year 111 BC, regulating the possession of public land in Italy and in the provinces of Africa and Greece (lex agraria).

4 Lex Camelia de XX quaestoribus

Bronzo - 81 a.C. - Roma, già Collezione Farnese - Inv. 2637 (CIL I2, 587) - La tavola fu trovata insieme alla Lex Antonia de Termessibus nel XVI secolo a Roma, nelle rovine del Tempio di Saturno, ai piedi del Campidoglio. Sono visibili i fori dei chiodi per l’affissione. Si tratta dell’unica tavola superstite della legge proposta nell’81 a.C. ai comizi tributi dal dittatore Lucio Cornelio Silla, che elevava il numero dei questori a 20, e riordinava le norme relative a questa magistratura. È la tavola ottava, come mostra la numerazione nell’angolo superiore sinistro: “VIII de XX q(uaestoribus)” e probabilmente la penultima: lo si può dedurre dalla praescriptio, incisa a lettere capitali in una sola linea continua lungo tutte le tavole, la quale precedeva la legge e ne riportava elementi di identificazione, come il magistrato proponente, il giorno della votazione, l’unità che ha votato per prima e il cittadino che per primo pronunciò il suo voto. Di questa legge Cornelia ci parla anche Tacito. La questura è una magistratura minore, il numero dei questori, all’origine di due, fu successivamente aumentato in connessione con le esigenze dell’espansione romana. La competenza dei questori era stabilita anno per anno da un senatoconsulto, all’inizio della carica. La loro funzione, in origine di ordine processuale, fu poi prevalentemente di ordine finanziario. Undici questori erano addetti alle province, due alla Sicilia, e uno per ogni altra, con poteri di ordine militare, amministrativo e finanziario. La tavola ottava, iscritta su due colonne, con i capita legis non numerati, tratta dell’aumento - contemporaneamente a quello dei questori - delle scuderie degli apparitores (scribae, viatores et praecones) quaestorii, cioè del personale che collabora con i magistrati; essi devono essere eletti per due terzi non dai magistrati che li hanno al loro servizio, bensì dai questori dei tre anni precedenti.

4 Lex Cornelia de XX quaestoribus

Bronze - 81 BC. - Rome, formerly in the Farnese collection - Inv. 2637 (CIL I22, 587). - Found in Rome in the XVI century, together with the Lex Antonia de Termessibus, among the ruins of the Temple of Saturn, at the foot of the Capitol. It has holes for the nails by which it was affixed. This is the only surviving table of the law proposed in 81 BC to the comitia tributa by the dictator Lucius Cornelius Silla, raising the number of quaestors to 20 and modifying the norms regulating this magistrateship. The inscription in the left upper corner indicates that it is the eighth table “VIII de XX q(uaestoribus)”, and probably the next to last, as can be deduced by the praescriptio, incised in capital letters in a single continuous line along all of the tables. The praescriptio preceded the law, and included elements of identification, such as the magistrate proposing the law, the day of the vote, the unit that had voted first and the citizen who had first stated his vote. This Lex Cornelia is also mentioned by Tacitus. Quaestorship was a minor magistrateship. The number of quaestors, originally two, was increased according to the needs of Roman expansion. The powers and tasks of quaestors were fixed year by year, at the beginning of their office, by a decree of the Senate (senatus consultum). Their function was originally judicial; later on, it became mainly financial. Eleven quaestors with military, administrative and financial powers were assigned to the provinces, two to Sicily and one to each of the others. The eighth table is inscribed on two columns, and the capita legis are unnumbered. It contains that part of the law establishing the increase - contemporaneous with that of the quaestors - of the decuries of the apparitores quaestorii (scribae, viatores et praecones), i.e. of the personnel collaborating with the magistrates, and that they must be elected by two thirds, not by the magistrates whom they serve, but by quaestors of the previous three years.

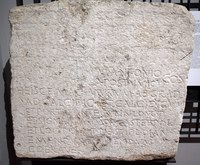

5 Tabula Bantina

Lastra di bronzo divisa in più parti II-I secolo a.C. - Oppido Lucano (Potenza), antica Bantia (1790) - Inv. 2554 (CIL I2, 583(=IX,416). - La lastra è incisa su entrambe le facce: da un lato è riportata, in latino, una legge votata dai comizi romani tra il 123 e il 100 a.C., dall’altro un testo in lingua osca e alfabeto latino. Il ritrovamento nel 1967 di un ulteriore frammento presso il Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Venosa, ha permesso di accertare con sicurezza che il testo osco è più recente di quello latino. Si tratta di alcune disposizioni che regolavano la vita pubblica nella comunità di Bantia agli inizi del I secolo a.C., come per esempio le modalità di celebrazione dei processi di fronte all’assemblea, il censimento dei cittadini e le relative sanzioni per chi si sottraeva alla registrazione, il cursus honorum dei magistrati locali. Sono norme influenzate dal diritto romano, tanto nella forma quanto nei contenuti, e si ipotizza che siano riprese dallo statuto della vicina colonia latina di Venusia (oggi Venosa).

5 Tabula Bantina

Bronze tablet divided into several parts 2nd-1st century BC. - Oppido Lucano (Potenza), ancient Bantia(1790) - Inv. 2554 (CIL I2, 583 (=IX,416). - The slab is incised on both faces. On one side is an act of law voted by the Roman comitia between 123 and 100 BC, in Latin, on the other a text in the Oscan language and the Latin alphabet. Thanks to the discovery in 1967 of another fragment of this document at the Museo Archeologico Nazionale of Venosa, scholars have been able to prove that the Oscan text is more recent than the Latin one.The Oscan text details some norms regulating several aspects of public life in the community of Bantia in the early first century BC, including the holding trials in front of the assembly, the taking of the census of the citizenry, with the attending sanctions for those who eluded registration, and the cursus honorum of local magistrates. These norms are influenced by Roman law, both in form and in content, and may be patterned after norms in the statute of the nearby Latin colony of Venusia (present-day Venosa).

6 Lex municipii Tarentini

Bronzo - I secolo a.C. - Taranto (1894) - Inv. 124320 (CIL I2, 590). - La lastra contiene parte dello statuto municipale di Taranto, databile tra l’89 e il 62 a.C. La città greca di Taranto, foederata con Roma, fu promossa a municipium dopo la guerra sociale con la concessione della cittadinanza. La parte conservata del documento (corrispondente alla nona tavola della lex) detta norme relative alle sanzioni da applicare nei casi di peculato, alle garanzie che devono prestare i magistrati che entrano in carica o i candidati alle magistrature, al peculiare requisito di censo necessario per far parte del senato locale. Sono inoltre previste norme che regolano vari aspetti pratici dell’amministrazione cittadina, quali la demolizione di edifici, la costruzione e la manutenzione di strade, canali di scolo e fogne. Il testo si interrompe nel punto in cui è trattata la procedura da seguire in caso di trasferimento dei cittadini del municipio (municipes).

6 Lex municipii Tarentini

Bronze 1st century BC. – Taranto (1894). - Inv. 124320 (CIL I2, 590) . - The slab carries part of the municipal statute of Tarentum. It is datable between 89 and 62 BC. The Greek city of Tarentum, foederata with Rome, was promoted to municipium after the Social Warand its citizens were granted Roman citizenship.The preserved part of the document (the ninth table of the lex) details norms relative to sanctions to be applied in cases of peculate, guarantees magistrates entering office or candidates to magistrate positions must provide, and wealth requirements for being eligible for the local senate. It also carries norms regulating various aspects of town administration, such as the demolition of buildings and the construction and maintenance of streets, drains, and sewers. The text breaks off where it deals with the measures to be taken in case “citizens of the municipium” (municipes) moved to another town.

7 Cippo graccano

Calcare - 132-131 a.C. - Atena Lucana (Salerno). - Inv. 124222 (CIL I2,639). - Il cippo di Atena Lucana è stato rinvenuto nel 1896; la base grezza era infissa nel terreno; sulla superficie cilindrica sono i nomi dei triumviri, nell’ordine Gaio Sempronio Gracco, Appio Claudio Pulcro e Publio Licinio Crasso (subentrato a Tiberio nel luglio del 133), e l’indicazione della loro carica (Triumviri A[gris] I[udicandis] A[dsignandis]; sul lato opposto è indicato il K(ardo) VII, mentre sulla faccia superiore sono incise due linee ad angolo retto (la decussis) indicanti i due assi della centuriazione, il Decumanus e il Kardo, che si incrociavano nel punto in cui era infisso il cippo e - vicino ad una delle due linee - una lettera D, interpretata come indicazione del decumanus.

7 Cippus

Limestone - 132-131 BC. - Atena Lucana (Salerno) - Inv. 124222 (CIL I2,639). - The cippus of Athena Lucana was found in 1896, is made of local limestone. Its rough base was planted into the ground. On its cylindrical surface are engraved the names of the triumviri Gaius Sempronius Gracchus, Appius Claudius Pulcher and Publius Licinius Craccus (who took Tiberius’ place in July 133), in that order, and the indication of their office (Triumviri A[gris[ I[udicandis] A[dsignandis]). On the opposite side is the indication K(ardo) VII, while, on the upper face, are two incised lines forming a right angle (the decussis), indicating the two axes of centuriatio, the Decumanus and the Kardo, which crossed at the point in which the cippus was erected. Near one of the lines is the letter “D”, interpretable as “decumanus“.

8 Cippo pomeriale di Ottaviano

Travertino - 36 a.C. - Santa Maria Capua Vetere (Caserta). - Inv. 3956 (CIL X, 3825, 4).

“Da qui passò l’aratro, per ordine di Cesare Imperator”.

Il cippo è relativo all’ampliamento del pomerium della colonia di Capua da parte di Cesare Ottaviano, figlio adottivo di Giulio Cesare e futuro Augusto. La colonia era stata dedotta nell’agro campano da Giulio Cesare nel 59 a.C., ex legge Iulia, e fu ampliata da Ottaviano nel 36 a.C. Il pomerium è il cerchio che delimita lo spazio della città, la zona religiosa destinata all’abitato, posta sotto la protezione divina, cioè inaugurata; questa delimitazione dei confini per mezzo di una linea sacra è uno dei riti più antichi delle popolazioni italiche, derivato dagli Etruschi. Tutta una serie di attività poteva compiersi solo fuori o solo all’interno del pomerio. Sui cippi che delimitavano questo tracciato era indicato, su uno dei lati, il numero che essi portavano nella sequenza delle pietre della medesima specie. Su un altro lato si ritrova il nome dell’imperatore al nominativo con i titoli e la formula di rito. La formula qui riportata fa riferimento al solco qua aratro ductum est. Richiama la formula che si legge nella lex coloniae Genetivae Iuliae, statuto municipale della colonia di cittadini romani dedotta ad Ossuna in Spagna iussu C. Caesaris, al capitolo 73 (sul divieto di introdurre cadaveri all’interno dei confini della colonia): ne quis intra fines oppidi coloniaeve, qua aratro circumductum erit, hominem mortuum inferto.

8 Pomerial cippus

Travertine - 36 BC. - Santa Maria Capua Vetere (Caserta). - Inv. 3956 (CIL X, 3825, 4).

“ Here the plough was drawn, by order of the imperator Caesar”. This cippus was placed to mark the extending of the pomerium of the colony of Capua by Caesar Octavian (who later took the name of Augustus), adoptive son of Julius Caesar. The colony was founded in the Campanian ager by Julius Caesar in 59 BC, ex lege Iulia, and was extended by Octavian in 36 BC. The pomerium was the limit of the urban space, the sacred living area, placed under divine protection, i.e. “inaugurated”. The marking of the city limits by means of a sacred line is one of the most ancient rites of the Italic peoples, and is of Etruscan origin. There were many activities that could be carried out only within or without the pomerium. On one of the sides of the cippi delimiting this area was a number indicating their position within the series of boundary stones they belonged to. On the other side, was the name of the Emperor, in the nominative case, accompanied by his titles and the ritual formula. The formula employed here refers to the furrow qua aratro ductum est. It echoes the formula used for the lex coloniae Genetivae Iuliae, the municipal statute of a colony of Roman citizens founded at Ossuna in Spain iussu C. Caesaris, more specifically chapter 73 (on the prohibition to bring corpses within the boundaries of the colony): ne quis intra fines oppidi coloniaeve, qua aratro circumductum erit, hominem mortuum inferto.

9 Pagus Herculaneus

Calcare locale - 94 a.C. - Recale (Caserta) - Inv. 3944 (CIL I2, 682 = X, 3772)

“Il pago Erculaneo ha decretato il 14 febbraio che il collegio dei magistri di Giove Compago spenda il denaro in base alla legge del pago nel restauro del portico del pago, sotto l’arbitrato del magister del pago Gneo Letorio figlio di Gneo. Ha decretato inoltre che il suddetto collegio dei magistri di Giove Compago abbia il proprio posto in teatro quando si tengono i giochi”. “...Nell’anno dei consoli Gaio Celio Caldone figlio di Gaio e Lucio Domizio Enobarbo figlio di Gneo”. (94 a.C.).

Dal territorio di Capua provengono circa trenta epigrafi di età repubblicana, relative ad opere di edilizia pubblica, civile e religiosa, curate da collegi di magistri intitolati alle divinità oggetto di particolare culto nella zona. Questa epigrafe è ricca di informazioni sull’amministrazione di Capua e del suo territorio nel periodo in cui la città fu privata del suo status politico (211-58 a.C.): il pagus (distretto rurale) Herculaneus aveva un’assemblea popolare, un proprio magistrato, leggi proprie, e decretava su questioni che riguardavano la città: il teatro di cui si parla è quello di Capua.

9 Pagus Herculaneus

Local limestone - 94 BC. - Recale (Caserta) - Inv. 3944 (CIL I2, 682 = X, 3772)

“The Pagus Herculaneus has decreed. on February 14, that the board of the magistri of Jupiter Compagus shall spend the money according to the law of the pagus, to restore the portico of the pagus, under the direction of the magister of the pagus Cnaeus Letoris, son of Cnaeus. It has further decreed that the above mentioned board of magistri of Jupiter Compagus shall have its place at the theater when the games are held”. - “...In the year of the consuls Caius Celius Caldus son of Caius and Lucius Domitius Henobarbus son of Cnaeus”. (94 BC) - The territory of Capua has yielded about thirty epigraphs of the Republican age, dealing with the erection of public buildings, both civil and religious, under the surveillance of boards of magistri named after deities having a special cult in the area. This epigraph gives a wealth of information on the administration of Capua and of its territory in the period in which the city was deprived of its political status (211-58 BC): the pagus (rural district) Herculaneus had a popular assembly, its own magistrate and laws, and the faculty to issue decrees on questions that regarded the city. The theater mentioned in the inscription is that of Capua.

10 Cippo

Tufo - II secolo a.C. - Santa Maria Capua Vetere (Caserta) - Inv. 3948 (CIL I2, 1581 = X, 3807)

L’iscrizione ricorda un culto di Giunone Lucina secondo i sacra Tuscolana. “Altare sacro a Giunone Lucina di Tuscolo”. Giunone assume con l’epiteto di Lucina la funzione di divinità che sovraintende alle nascite, proteggendo le donne al momento del parto; l’origine del nome sembra riportare a lux, la luce della luna che regola i cicli vitali. L’ara tu ritrovata insieme ad un’altra uguale per forma in onore di Ercole. Questa circostanza documenta lo stretto legame esistente tra Ercole e Giunone Lucina, che condividono la funzione di divinità fecondatrici.

10 Cippus

Tuff – 2nd BC. - Santa Maria Capua Vetere (Caserta) - Inv. 3948 (CIL I2, 1581 = X, 3807)

The inscription concerns a cult of Juno Lucina, celebrated according to the rites of the sacra Tuscolana. Juno, with the epithet of “Lucina”, is the deity who watches over child-bearing, protecting women at the moment of delivery. The name “Lucina” apparently derives from lux, the moonlight that regulates life-cycles. The altar was discovered with another of the same form, dedicated to Hercules, a find that confirms the existence of a close connection between Hercules and Juno Lucina, who both have the function of fertility gods.

11 Blocco

Calcare - 99 a.C. - Sant’Angelo in Formis (Caserta) - Inv. 3943(CIL I2, 680= X, 3781).

“Nell’anno dei consoli M. Antonio e A. Postumio questi magistri curarono, con i fondi della cassa del santuario di Diana, la costruzione del muro dalla gradinata al calcidico, del calcidico, del portico lungo (...) davanti alle cucine, delle statue marmoree di Castore e Polluce, e l’acquisto di luoghi privati”.

Il santuario era situato alle pendici del monte Tifata, punto strategico per il controllo della piana di Capua, frequentato fin dal IX secolo a.C.. Le fonti letterarie facevano risalire il culto di Diana alla fondazione di Capua, e vantavano la grande antichità del santuario. In realtà le attuali conoscenze archeologiche consentono di risalire per le strutture del tempio al massimo al IV-III secolo a.C. Il santuario gode di grande prestigio: i suoi confini furono fissati da Silla nell’83 a.C., e quando sorsero controversie intervennero direttamente gli imperatori Augusto e Vespasiano. Un’iscrizione lacunosa nel pavimento a mosaico del tempio, parzialmente conservato nella chiesa, ricorda radicali lavori di ristrutturazione del tempio curati dai magistri, sempre attingendo dalla cassa del santuario. La cronologia di questi lavori e incerta in quanto la data consolare riportata nell’iscrizione e andata in parte perduta: essa potrebbe rifarsi al 74 a.C. o, come e stato suggerito più recentemente, al 108 a.C., cronologia più consona alle caratteristiche stilistiche del mosaico.

11 Block

Limestone - 99 BC. - Sant’Angelo in Formis (Caserta) - Inv. 3943 (CIL I2, 680= X,3781)

“In the year of the consuls M. Antonius and A. Postumius, these magistri supervised, with the funds from the treasury of the sanctuary of Diana, the construction of a wall from the staircase to the chalcidicum, of the chalcidicum (itself), of the long portico (...) in front of the kitchen, of the marble statues of Castor and Pollux, and the purchase of private places”.

The sanctuary was placed at the base of Mount Tifata, a strategic position controlling the plain of Capua, frequented as early as the 9th century BC. According to the literary sources, the cult of Diana goes back to the foundation of Capua, and the sanctuary was hence very ancient. Present-day archaeological research, however, has proved that the temple building cannot be earlier than the 4th or 3rd century BC. The sanctuary enjoyed a great prestige. Its boundaries were fixed by Silla in 83 BC and, when controversies arose, the emperors Augustus and Vespasianus intervened personally. A mutilated inscription on the mosaic floor of the temple, partially preserved inside the present-day church, commemorates the radical restructuring of the temple carried out under the supervision of the magistri with funds from the sanctuary’s treasury. The chronology of these building works is uncertain, as the consular date contained in the inscription is partially lost. It could be 74 BC or, as it has been suggested more recently, 108 BC, a date that agrees better with the stylistic characteristics of the mosaic.

12 Frammento di architrave, recante due iscrizioni

Calcare locale - I secolo a.C. San Prisco (Caserta) - Inv. 3945 (CIL I2, 685-686)

L’epistilio doveva essere situato nel teatro di Capua: l’iscrizione originaria, ricordava come un collegio di magistri: “aveva fatto sì che si costruissero due settori verticali (cunei) della cavea”.

Il teatro di Capua fu costruito tra il 112 e il 94 a.C. Un’impresa del genere poteva essere affrontata da una comunità economicamente florida; si pensi che Roma avrà un suo teatro in pietra solo quarant’anni più tardi. Il teatro di età repubblicana fu in seguito sostituito o affiancato da un altro, costruito non prima dell’età augustea. Quando già era spezzato, l’epistilio fu riutilizzato per l’iscrizione più recente: “... Questi magistri, in base ad un decreto del pago, raccolsero tra loro la somma necessaria (oppure: contribuirono) per l’acquisto di uno schiavo di Giunone Gaura, nell’anno dei consoli Publio Cornelio Lentulo e Gneo Aufidio Oreste”. (71 a.C.). I santuari, dunque, in questo caso quello di Giunone Gaura, oltre a una propria cassa, possedevano anche un proprio corpo di schiavi.

12 Fragment of an architrave, with two inscriptions

Local limestone - 1st BC. - San Prisco (Caserta) - Inv. 3945 (CIL I2, 685-686)

The epistyle must have belonged to the theater of Capua: the original inscription related that a board of magistri “had two vertical sectors (cunei) of the cavea built”.

The building of the theater of Capua began in 108 BC, as we know from an inscription referring to the contract assigned by the magistri of Jupiter Optimus Maximus for the construction of the embankment on which the cavea was to rest, and was already finished by 94 BC, the year of the inscription of the pagus Herculaneus, which implies that the theater was in function. Such an enterprise could only have been carried out by an economically florid community, considering that Rome had a stone-built theater of its own only forty years later. The Republican age theater was later replaced or integrated by another one, built no earlier than the Augustan age.

When it was already broken, the epistyle was reused for a more recent inscription: “...These magistri, by decree of the pagus, collected among themselves the sum necessary for (or: contributed to) the purchase of a slave of Juno Gaura, in the year of the consuls Publius Cornelius Lentulus and Cnaeus Aufidius Orestes”. (71 BC) Sanctuaries, therefore (in this case the sanctuary of Juno Gaura), besides having their own treasury also possessed their own slaves.

13 Colonna miliaria

Marmo - 102 d.C. - Napoli - Inv. 250176 (CIL X, 6926)

Il miliario indica il V miglio della via da Pozzuoli a Napoli attraverso le colline del Vomero e dei Camaldoli, iniziata da Nerva e compiuta da Traiano, di cui si riporta la titolatura ufficiale che permette di datare con precisione la colonna. Per indicare sulle strade pubbliche le distanze da percorrere o quelle percorse, era uso mettere, in genere ogni mille passi (circa 1480 metri), delle pietre generalmente di forma cilindrica, a volte quadrangolare. Su alcuni di questi cippi miliarii è indicata solo la cifra del numero di migliaia di passi dall’inizio o dalla fine della strada stessa, o da Roma; altri contengono - oltre a queste - diverse altre informazioni, per lo più il nome e la titolatura dei magistrati o dell’imperatore che avevano fatto costruire o restaurare la via, o notizie particolari sui lavori e sulle spese fatte.

13 Milliary column

Marble - 102 AD. – Napoli - Inv. 250176 (CIL X, 6926)

This milepost marks mile V of the road going from Puteoli to Neapolis though the hills of Vomero and Camaldoli, whose construction was initiated by Nerva and completed by Trajan. The latter’s official titles are engraved on the column, enabling us to date it with precision. To mark the distances traveled or to be traveled on public roads, the Romans used to place milestone, mostly cylindrical, occasionally square, generally every thousand paces (about 1480 meters). Some only bear a figure indicating the number of thousands of paces from the beginning or the end of the road itself, or from Rome, while others also provide additional information, mostly the name and titles of the magistrates, or specific information on the building of the road, or its cost.

14 Menologium rusticum Colotianum

Marmo - I secolo d.C. - Roma, dalla collezione Farnese, già in quella dell’umanista Angelo Colussi (XVI secolo) - Inv. 2632 (CIL VI, 2305).

La superficie delle quattro facce è divisa in dodici colonne (tre per lato) corrispondenti ai mesi, secondo il sistema in uso nel I secolo d.C. Per ciascun mese sono indicati i giorni, le nonae (quinto e settimo giorno a seconda del mese) la lunghezza del giorno e della notte, il segno zodiacale, il nume tutelare, i lavori agricoli e le feste principali. Questo è uno dei due soli esempi di calendari agricoli romani che ci siano pervenuti.

14 Menologium rusticum Colotianum

Marble – 1st century AD. - Roma, from the Farnese collection, previously in that of the humanist Angelo Colussi (16th century) - Inv. 2632 (CIL VI, 2305)

The text on the four faces is distributed into twelve columns, three per face, corresponding to the months, according to the system used in the 1st century BC. For each month, the days are indicated, as well as the nonae - fifth or seventh day of the month -, the length of day and night, the sign of the Zodiac, the tutelary deity, agricultural chores, and the main festivals. This is one of the only two surviving Roman agricultural calendars.

15 Fasti Allifani

Marmo - Fine I secolo a.C. - inizi I secolo d.C. - Alife (Caserta) - Inv. 3005-3006 (CIL IX, 2318 e 2319).

La lastra in frammenti appartiene a un calendario risalente all’età augustea o di poco successivo. Un frammento è relativo ai mesi di luglio e di agosto. L’altro contiene nomi di popoli e potrebbe appartenere a un calendario pubblico con l’elenco delle nundinae. Un altro frammento (CIL IX, 2320) è conservato nel Museo Provinciale Campano di Capua.

15 Fasti Allifani

Marble - Late 1st century BC-early 1st century AD. - Alife (Caserta). - Inv. 3005-3006 (CIL IX, 2318 and 2319).

This fragmentary slab belongs to a calendar dating back to the age of Augustus or slightly later.The fragment is relative to the weeks of July and August.The other contains names of peoples and may belong to a public calendar with a list of nundinae. Another fragment (CIL IX, 2320) is kept at the Museo Provinciale Campano in Capua.

16 Fasti Farnesiani

Marmo. I secolo d.C. - Roma, dalla collezione Farnese. - Inv. 2633 (CIL VI, 2301)

Contiene alcune notazioni per i mesi di febbraio e marzo. A sinistra di ciascuna colonna sono indicati i giorni per mezzo delle cosiddette lettere nundinali (A-H) seguite dall’indicazione delle festività e da sigle che indicano la qualità dei giorni.

16 Fasti Farnesiani

Marble. 1 st century AD. - Rome, from the Farnese collection. - Inv. 2633 (CIL VI, 2301)

Carries some entries for the months of February and March. To the left of each column are indicated the days, by means of the so-called nundinal letters (A-H).The nundinal letters are followed by the indication of holidays and by acronyms indicating the character of the days.

17 Index nundinarius

Marmo. I secolo d.C. - Forse da Lazio meridionale. - Inv. 2635 (CIL VI, 32505)

Il testo riporta le località e i giorni in cui si svolgevano i mercati a periodicità regolare. In alto vi sono i nomi dei giorni della settimana da Saturno a Venere; nel rosone i giorni del mese lunare; sulla destra le città e accanto i fori in cui si inserivano i chiodi per indicare giorno e luogo di mercato. Vi è anche l’indicazione delle stagioni (qui solo l’estate e l’inverno) e della loro durata.

17 Index nundinarius

Marble.1 st century AD. - Possibly from southern Latium. - Inv. 2635 (CIL VI, 32505)

Lists of the places and days for the regular holding of markets. In upper there are the names of the days of the week, from Saturn to Venus; in the rosette, are the days of the lunar month, on the right the towns, and beside them the holes in which nails were placed to indicate the day and place of the market. The seasons and their duration was also indicated; only summer and winter remain here.

18 Feriale campano

Piano di una mensa o ara con cornice a fascio di foglie. - Rinvenuta nell’anfiteatro nel 1829, riutilizzato per incidervi l’iscrizione. – Marmo. - 387 d.C. - Santa Maria Capua Vetere (Caserta). - Inv. 3954 (CIL X, 3792).

Questo calendario municipale contiene una ordinanza per a Campania, del 387 d.C., con data e nome delle feste che devono essere celebrate durante l’anno ( da qui il nome di feriale). Sono feste politiche, familiari, rurali di cui è rilevante piuttosto la funzione per cui sono celebrate che non la divinità che viene invocata; sono dunque tali da non offendere il sentimento dei Cristiani, e anche nel nome attenuano il legame con le analoghe antiche feste pagane.Poco dopo, la costituzione di Teodosio del 389 sopprimerà il calendario pagano e le sue feste, sancendo la fine del loro ruolo pubblico, e vi sostituirà le domeniche e le feste del culto cristiano.

18 Feriale campanum

Reused table of an altar or mensa with a leaf bundle frame, found in 1829 in the amphitheater. – Marble - 387 BC - Santa Maria Capua Vetere (Caserta) - Inv. 3954 (CIL X, 3792).

This municipal calendar contains an ordinance for Campania, dated 387 BC, with the date and name of the festivals to be celebrated during the year (hence the name of feriale). These festivals were essentially political, family or rural celebrations, and their function was more relevant than the deity invoked, and thus did non offend the feelings of the Christians. Their names reflect a weakening of the ties with the corresponding ancient pagan festivals. Soon after, Theodosius’ constitution (389 AD) suppressed the pagan calendar and its festivals, sanctioning the end of their public role, and replaced it with the Sundays and festivals of the Christian cult.

Fotografie di Giorgio Manusakis