Sala LXXIII

I temi mitologici

Nella seconda metà del I sec. d. C. il repertorio delle storie raffigurate in pittura si amplia notevolmente: nuovi temi compaiono accanto a quelli ‘tradizionali’, e i personaggi che avevano incarnato lo spirito eroico dell’età augustea diventano i protagonisti di quadri che mostrano aspetti diversi delle loro vicende, con una marcata preferenza per temi narrativi o ‘di evasione’.

Godono grande favore temi sconosciuti nella tradizione figurativa precedente: il mito più frequentemente rappresentato nei quadri degli ultimi decenni della vita dei centri vesuviani è quello di Narciso. La storia del giovane condannato dagli dei a innamorarsi della propria immagine riflessa nell’acqua e a perire nel tentativo di raggiungerla, è presente a Pompei in più di 40 esemplari, concentrati in un arco di tempo limitato. È spesso associato ad altri temi di amore, come la figura femminile che pesca in compagnia di un gruppo di amorini (la c.d. pescatrice), o Endimione, il giovane cacciatore amato da Selene.

Storie come quelle di Teseo o Perseo subiscono un notevole cambiamento iconografico: al Teseo trionfatore o ‘rifondatore’, si sostituisce il momento molto più intimo e privo di connotazioni eroiche. in cui Arianna, da lui abbandonata, si risveglia in lacrime sulla spiaggia di Nasso mentre la nave su cui egli è fuggito si allontana all’orizzonte. Anche la storia di Perseo e Andromeda viene presentata sotto un altro aspetto: al gesto cavalleresco di Perseo che aiuta la giovanetta a liberarsi dalle catene, si sostituisce la coppia di amanti seduti e abbracciati, riconoscibili, - tra le tante coppie della pittura della fine del I sec. d.C. tra le quali c’è anche quella divina di Marte e Venere. - solo grazie all’attributo della testa di Medusa che l’eroe solleva. Si è ora interessati a rappresentare genericamente una storia piuttosto che a rappresentare le imprese di determinati miti.

Si tende ad abbandonare le vicende il cui contenuto tragico e altamente morale la punizione inflitta dagli dei a colui che si ribella ai limiti umani, non rendeva possibile una lettura diversa e più distesa, e così la storia di Icaro che precipita al suolo perché ha volato troppo vicino al sole, che era stata il soggetto di alcuni dei quadri più belli conservati a Pompei, nell’ultima fase della vita della città è presente in due soli esempi. Continua la diffusione di quadri con episodi legati alla guerra di Troia: dagli antefatti, come il Giudizio di Paride, alla preparazione, come il sacrificio di Ifigenia, il ritrovamento di Achille a Sciro, la forgiatura delle armi dell’eroe e la consegna delle stesse a Teti, fino all’introduzione del cavallo nelle mura di Troia nonostante i funesti presagi di Laocoonte e Cassandra, fino allo notte dell’incendio, tutte dolorose indispensabili premesse perché Enea giungendo nel Lazio desse poi origine a Roma.

La narrazione ora abbandona i personaggi secondari per concentrarsi sui soli protagonisti, aumentando in tal modo l’effetto drammatico. Scompaiono le personificazioni di luogo o gli astanti stupiti, che caratterizzavano i quadri della prima età imperiale e che, volgendo a volte lo sguardo verso l’osservatore, facevano da ponte tra il dentro e il fuori del quadro, o le vaste ambientazioni paesistiche nelle quali la storia narrata sembra costituire il pretesto per un’ambientazione fantastica, che avevano rappresentato una importante caratteristica dei quadri dei decenni precedenti.

Mythological themes

in the second half of the 1st century AD the repertoire of stones depicted if i paintings grew notably. New themes appeared alongside ‘traditional’ ones, and the characters who had embodied the ‘heroic’ spirit of the Augustan age became the protagonists in paintings that revealed different aspects of their stones, there was a marked preference for narrative or ‘escapist’ themes.

Themes unknown in the previous figurative tradition now enjoyed great popularity, the most frequently depicted myth in the paintings of the last decades of life of the Vesuvian cities is that of Narcissus. The story of the young man condemned by the gods to fall in love with his own image in the water and perish in the attempt to reach it is seen at Pompeii more than 40 times, and all painted within a short chronological period. Narcissus is often associated with other love themes, such as the female figure who fishes in the company or a group of cupids (the so-called ‘fishing-woman’), or Endymion, the young hunter beloved of Selene.

Stories such as that of Theseus or Perseus underwent notable iconographic changes; in the place of the ‘triumphant’ or rebuilder Theseus were substituted more intimate moments, without heroic connotations. Thus Ariadne, abandoned by Theseus, awakens in tears on the beach of Naxos while the ship on which he flees disappears into the distance. The story of Perseus and Andromeda is also presented differently the noble gesture of Perseus who helps to free the young girl from chains is replaced by the pair of seated and embracing lovers who are recognizable (from among the many couples in the paintings of the end of the 1st century AD such as the divine couple Mars and Venus) only because the hero hold up the head of Medusa. Instead of the deeds or events of particular myths, stories are now being depicted in more general terms There was o tendency to abandon the stories whose tragic end or high moral content the punishment inflicted by the gods to whornever rebelled against human limits did not allow a different or expanded interpretation thus the story of Icarus who fell to the earth because he flew too close to the sun the subject of several beautiful paintings of Pompeii, is only found twice in the last phase of the city's life. But the number of paintings relating to episodes connected with the Troian War grew the events leading up to it such as the Juagment of Paris the preparation for it, such as the Sacrifice of Iphigenia, the Discovery of Achilles at Skyros, the Forging of the Hero's Weapons and their Delivery to Thesis, up to the entrance of the wooden horse into the walls of Troy, and including the tragic prophecies of Laocoon and Cassandra, until the night of the fire. These were all painful but necessary events that paved the way for Aeneas to reach Latium in preparation for the foundation of Rome.

Narration now abandons secondary characters and focuses on the main protagonists, thus increasing the dramatic effect.

The background figures and amazed spectators who characterized the paintings of the early imperial period disappear. By turning their gaze on the observer these figures had created a ‘bridge’ between the interior and exterior of the paintings. The vast landscapes within which stories had taken place that had created a pretext for fantastic setting and which were an important characteristic of the paintings of the previous decades also disappear.

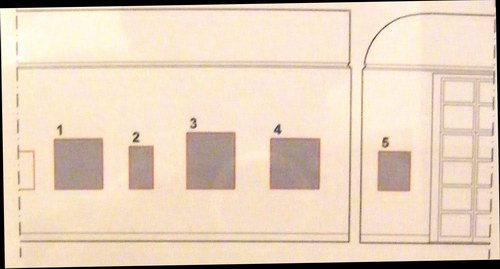

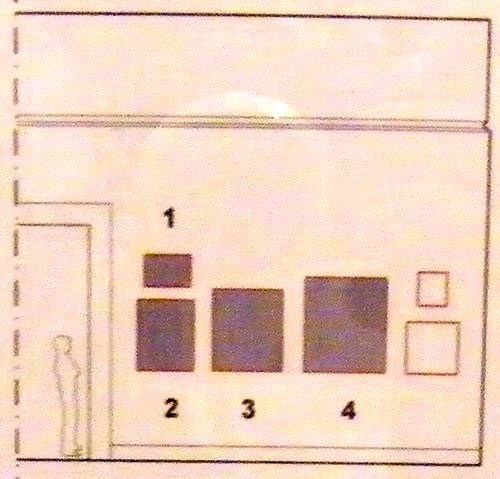

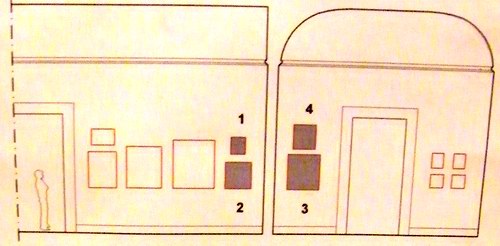

Parete 1

Nell'atrio della Casa del Poeta tragico, una dimora di medio livello, che conserva ancora un interessante apparato decorativo di mosaici e affreschi, si trovavano grandi quadri classistici, di impianto aulico, con temi legati alla Guerra di Troia e alle principali divinità (Zeus, Hera, Afrodite e Poseidone), le cui collocazioni sono note da tempere di F. Morelli eseguite prima del distacco. Nel tablino si trovano il quadro con la storia di Alcesti, la regina che accetta di morire in luogo del marito e che Eracle riporterà dagli inferi e, nel pavimento, il mosaico da cui la casa prese nome. Nel peristilio si trovava il quadro con la scena del sacrificio di Ifigenia, nel quale a personaggi derivati da modelli greci, come l'indovino Calcante, Agamennone che si copre gli occhi inorridito dall'atto che ha dovuto compiere, o il gruppo di Ulisse e Diomede che trascinano la fanciulla, si aggiungono innovazioni dell'artista pompeiano quali la cerva e Diana tra le nuvole.

Fotografie di Giorgio Manusakis