MANN - Piano meno uno - Sezione Epigrafi

Sala CLIV

PUTEOLI

Durante la II guerra punica (218-202 a.C.) Puteoli fu una piazzaforte romana. Le caratteristiche favorevoli della costa, con acque profonde e senza rischi di insabbiamento, ne fecero lo scalo del grano destinato alle truppe di stanza in Campania e probabilmente, già da ora, anche alla plebe romana. Dopo la sconfitta di Annibale, per iniziativa di Scipione Africano, nel 199 a.C si istituì a Puteoli un dazio. Nel 194 a.C. sul promontorio di Rione Terra venne dedotta una colonia di cittadini romani, che presto si allargò alla fascia costiera con strutture portuali e commerciali: L’emporium. Qui non tardarono a stabilirsi gruppi organizzati di mercanti orientali che vi impiantarono i loro culti.

Già nel II secolo a.C. Puteoli era una città ricca e popolosa, crocevia di intensi traffici mediterranei. In seguito furono fatte deduzioni coloniali dagli imperatori Augusto (27 a.C.-14 d.C.), Nerone (54-69 d.C.) e Vespasiano (69-79 d.C.), che inaugura la dinastia dei Flavi. In queste occasioni il territorio della città fu ampliato.

Durante il regno di Augusto Puteoli mutò volto. La comunità manifestò il suo consenso al nuovo regime emulando il rinnovamento urbanistico della capitale. Come Roma, Puteoli divenne una “città di marmo”. Lucio Calpurnio Capitolino (n. 1) fece ricostruire il principale tempio cittadino sull’acropoli di Rione Terra. Qui si apriva il foro della colonia augustea, gremito di edifici pubblici finanziati dall’aristocrazia cittadina, come la Basilica di Augusto fatta costruire dalla famiglia degli Annii (n. 2). Il porto fu al centro della sistemazione augustea dell’annona di Roma. A quest’epoca risale il nuovo molo, ai piedi di Rione Terra, proteso in mare per circa 370 metri, sostenuto da imponenti piloni. Allo sviluppo urbanistico corrisposero riforme amministrative modellate su quelle attuate da Augusto a Roma, con la divisione della colonia in regiones e vici (nn. 5, 21).

La colonia neroniana del 60 d.C. è legata all’intervento imperiale a seguito di dissidi tra senato municipale e popolo. Nerone, ancora ai fini dell’annona di Roma, potenziò il Porto Giulio, costruito a fini militari nel 37 a.C. attorno al doppio bacino dei laghi Lucrino e Averno, a ovest di Pozzuoli, e in seguito riconvertito a scopi civili e diventato parte delle strutture portuali della ripa puteolana. Contemporaneamente, Nerone avviò il progetto, rimasto incompiuto, di un canale navigabile dal lago Lucrino al Tevere. È oggetto di discussione. quali siano le opere pubbliche da lui promosse. Nella guerra civile che seguì la morte di Nerone (69 d.C.) Puteoli parteggiò per Tito Flavio Vespasiano che, da vincitore, la insignì del titolo di colonia Flavia Augusta (n. 3). A questa epoca risale l’anfiteatro maggiore anche se si è ipotizzato che l’arena sia opera di Nerone, o che sia stata solo completata da Vespasiano. L’età flavia è decisiva per lo sviluppo urbanistico e la sistemazione del pianoro alle spalle di Rione Terra, ancora relativamente spoglio in età augustea e che già forse dalla fine dell’età claudia si popola di spazi forensi (il Foro Transitorio [n. 2], attribuito già all’età neroniana), edifici pubblici, complessi residenziali, servizi. Si trattava di una zona nevralgica della città: qui confluivano le vie per Napoli e Capua e la via Domiziana, voluta nel 95 d.C. da Domiziano (81-96 d.C., n. 5), figlio di Vespasiano, per rendere più diretti i collegamenti tra Puteoli e Roma.

Puteoli

During the 2nd Punic War (218-202 BC) Puteoli was a Roman stronghold; moreover its seafront, with deep water and free of sandbars, was ideal for the creation of a harbour. It became the landing-point for the grain supplies for troops stationed in Campania, and probably very soon also grain for Roman plebs. On the initiative of Scipio Africanus and his group an excise office was set up in Puteoli in 199 BC, and five years later a colony of Roman citizens was settled on the headland of Rione Terra. This new settlement rapidly spread along the coast as the commercial and port facilities of an emporium developed, and this in turn attracted organized groups of merchants from the east. By the middle of the 2nd century BC Puteoli was a rich and populous city, the hub for thriving trade ventures around the Mediterranean.

In the Imperial era the Roman population of Puteoli was increased by the introduction of colonies by Augustus (27 BC-14 AD), Nero (54-68 AD) and Vespasian (69-79 AD), who inaugurated the Flavian dynasty. On each occasion the city’s territory was enlarged.

Under Augustus Puteoli underwent a radical facelift. The local aristocracy demonstrated their support for the new regime by emulating the urbanistic renewal initiated by the princeps in Rome. Many monuments were built or upgraded, so that Puteoli too was transformed into a “marble city”. Lucius Calpurnius Capitolinus (n. 1) was responsible for the rebuilding of the city’s major temple on the acropolis of Rione Terra. Here, the Forum Augustan, was full of public buildings paid for by the city’s aristocracy, including the Basilica of Augustus, put up by the Annii (n. 2). The port was given a crucial role in Augustus’s organization of food supplies to Rome, which had become a megalopolis with as many as a million inhabitants. This is probably when the new pier was built at the foot of Rione Terra, projecting some 370 metres into the sea and resting on impressive pillars.

The urban expansion was accompanied by administrative reforms modelled on those carried out by Augustus in Rome: the territory was divided up into regions and vici (nn. 5, 21). The colony introduced by Nero in 60 AD was probably intended to put an end to hostilities between the municipal senate and the populace.

Again with an eye to guaranteeing food supplies to Rome, Nero developed Portus Julius, built for military purposes in 37 BC round the two lakes of Lucrinus and Avernus, west of Puteoli. Its military character was removed and it was incorporated into the harbour facilities of the ripa puteolana. Nero also began the construction of a navigable canal stretching from Lake Lucrinus to the River Tiber, but it was never completed, and we are not entirely sure for which other building works he was responsible. In the civil war which followed his death in 69 AD Puteoli sided with Titus FIavius Vespasianus, earning the new Emperors gratitude and the little of Colonia Flavia Augusta (3). This was when the larger amphitheatre was completed, on the natural terrace behind Rione Terra. The arena may have been built by Nero, and perhaps Vespasianus only put the finishing touches to the building. There is no doubt that the Flavian era was crucial for the urbanistic development and lay-out of terrace, which had not been particularly built on in Augustan times but which now acquired public buildings, residential developments and utilities. It was a strategic focal point in the city, at the intersection of the main roads from Naples and Capua, to which was added the Via Domitiana, created in 95 AD by Domitianus, son of Vespasianus, to improve communications between Puteoli and Rome.

LA CITTA NEL II SECOLO D.C.

Con il I secolo d.C. si esaurisce la stagione più vitale dell’aristocrazia puteolana e dell’economia della colonia. L’imperatore Traiano (98-117 d.C.) dota Roma di un porto alla foce del Tevere in grado di accogliere navi di grande stazza. Questo, nel corso del II secolo d.C. sostituirà Puteoli come punto di arrivo della “flotta alessandrina”, che trasportava il grano egiziano decisivo per l’approvvigionamento dell’Urbe. L’aristocrazia puteolana si rivolge alle sue proprietà fondiarie e, fuori della colonia, alle occasioni fornite dalla carriera politica. Ciononostante la prosperità, la densità demografica, il decoro urbano, i segni dell’attenzione imperiale non declinano. A Baia morì Adriano (117-138 d.C.), provvisoriamente sepolto a Puteoli. Il suo successore Antonino Pio (138-161 d.C) istituì in suo onore giochi quinquennali alla greca detti Eusebeia, per i quali fece costruire, all’estremità orientale della città, uno stadio per le gare ginniche. Antonino Pio completò anche il restauro dei piloni del molo. La sua memoria fu onorata dai Puteolani con l’erezione di un templum Divi Pii (n. 8) in cui si riuniva il senato cittadino. Alla stessa epoca risale anche il rifacimento del macellum (mercato dei generi alimentari) erroneamente denominato “tempio di Serapide”, nella città bassa, e un imponente edificio termale affacciato sul mare, noto come “tempio di Nettuno”.

The city in the 2nd century AD

By the end of the 1st century AD the golden age of the highly enterprising local aristocracy, who had procured an economic boom for the colony, was over. The emperor Trajan (98-117 AD) built a port for Rome at the mouth of the Tiber, suitable for ships with a large draught and not prone to silting up. During the 2nd century AD this port replaced Puteoli as the landing-point for the “Alexandrine fleet” bringing the grain supplies from Egypt which were vital to life in the capital. The aristocracy of Puteoli turned to its estates and the opportunities to be had in the wider world of politics. Nonetheless the city still bore all the marks of prosperity, with a high demographic density, fine urban decor and signs of imperial preference. The emperor Antoninus Pius (138-161 AD) was particularly active in the city. He succeeded Hadrian (117-138 AD), who had died at Baiae and received provisional burial in Puteoli, and instituted the quinquennial games in his honour known as the Eusebeia (or Pii) . He built a stadium at the eastern edge of the city for the gymnastic contests. In addition Antoninus completed the restoration of the pillars supporting the pier, which Hadrian had promised to carry out. The citizens of Puteoli honoured the memory of Antoninus by erecting the templum Divi Pii (n. 8) where sessions of the municipal senate were held. It was during the reigns of Hadrian and Antoninus that the macellum (food market, although commonly referred to as the “temple of Serapis”) and a large bathing establishment built in a commanding position below the natural terrace (whose ruins came to be known as the “temple of Neptune”) were both amply refurbished.

COMUNITÀ E CULTI ORIENTALI

Già nel II secolo a.C. sorgeva a Puteoli un tempio del dio egizio Serapide (n.11), nume tutelare dei mercanti alessandrini. Radicato era anche il culto della dea egizia Iside: le fiaschette vitree con vedute di Puteoli attestano ancora nel III-IV secolo d.C. l’esistenza di un suo tempio. Le epigrafi qui esposte sono relative al culto nabateo del dio Dusares (n. 12), al culto del “dio santo” da parte dei Fenici di Tiro (n. 17), ai culti sincretistici siriaci. La presenza organizzata di Arabi Nabatei e di Fenici a Puteoli, era legata all’importazione di beni di lusso, di cui essi erano produttori o intermediari. La documentazione sui Tiri esemplifica il funzionamento di queste comunità, caratterizzate da forte senso di identità. I Tiri avevano a Puteoli una base stabile (statio), la cui manutenzione, insieme alla celebrazione dei culti patrii (associati a quelli in onore dell’imperatore), era assicurata dai contributi di armatori e mercanti. Nel 174 d.C. i Tiri di Puteoli, in difficoltà, si rivolsero al senato della madrepatria, chiedendo un contributo: la richiesta fu accolta, perché il mantenimento della statio rientrava negli interessi di Tiro. Tra i siriaci, devoti di Giove Ottimo Massimo di Damasco (n. 20) e di Giove Ottimo Massimo di Eliopoli (nn. 18-19), poteva invece essere forte la presenza di soldati e schiavi. Va altresì ricordata la comunità giudaica, riferimento per i connazionali interessati a relazioni con il potere romano: in età neroniana ne fece esperienza lo storico Flavio Giuseppe quando, venuto a Roma per perorare la causa di sacerdoti fatti arrestare dal governatore di Giudea, trovò a Puteoli validi appoggi per avvicinare l’imperatrice Poppea.

Oriental cults and communities

As early as the 2nd century BC Puteoli had a temple to the Egyptian god Serapis (n. 11). Similarly long-lived was the cult of the Egyptian goddess Isis. The glass flasks dating from the 3rd-4th century AD bearing view of Puteoli show that her temple was still standing. The epigraphs displayed here are related to the Nabataean cult of the god Dusares (n. 12), the cult of the “holy god” worshipped by the Phoenicians of Tyre (n. 17), and the syncretic cults of Syriac communities. The presence of Nabataean Arabs and Phoenicians in Puteoli was due to the import business in luxury goods from the East in which they were involved as producers or intermediaries. The records we have referring to the natives of Tyre gives an idea of how these merchant communities functioned. Tyrians had in Puteoli their own trading and cult centre (statio). From a letter they sent to the senate of Tyre in 174 AD, we learn that the upkeep of the statio and the celebration of the native cults (associated with those in honour of the Emperor) were usually funded by contributions from ship owners and merchants. Among Syriacs, devotees of Jupiter Optimus Maximus Damascenus (n. 20) and Jupiter Optimus Maximus Heliopolitanus (nn. 18-19), there were a large number of soldiers and slaves. Puteoli had a influential Jewish community which maintained good relations with the authorities in Rome. It would have been a fundamental point of reference for all Jews who had any dealings with Rome. The Jewish historian Josephus, who went to Rome in about 64 AD to plead on behalf of Jewish priests who had been arrested by the governor of Judea, found influential supporters in Puteoli who were able to present him to Poppea, the wife of the Emperor.

ECONOMIA E SOCIETÀ

La stagione aurea (II sec .a.C.-I d.C.) dell’economia di Puteoli si basa sul porto che consentiva l’attracco di grandi navi mercantili, sulla vicinanza a Roma e sulle particolarità naturali della regione flegrea. Qui l’aristocrazia romana costruì lussuose ville marittime, costituendo quella villa society che d’estate confluiva sul golfo puteolano, senza mai dimenticare la politica romana e gli affari.

Per la mentalità romana un senatore poteva occuparsi solo della proprietà terriera, ma ciò che a Roma non era lecito, era più facile in area flegrea, dove banchieri e imprenditori erano pronti ad investire proficuamente i capitali disponibili.

Il commercio del grano aveva spinto dal II secolo a.C. mercanti campani sull’isola di Delo, fondamentale nei collegamenti con l’Egitto, massimo produttore di grano. A Delo si acquistavano anche schiavi, impiegati in agricoltura. I nuovi stili di vita dell’aristocrazia italiana accrebbero la richiesta di beni di lusso, importati dall’Arabia nabatea, dal Corno d’Africa, da Ceylon, dall’India. Queste rotte vedevano in prima linea i mercanti puteolani. Guadagni elevatissimi compensavano rischi e investimenti, cui partecipavano, accanto alla classe dirigente romana, anche le elites locali. Fioriva in parallelo un ceto imprenditoriale diffuso in tutti gli strati della società, con manifatture che raccoglievano l’eredità delle tradizioni manifatturiere capuane, producendo “merci di ritorno” per le navi che scaricavano a Puteoli. L’economia puteolana era diversificata, e prosperò anche quando il porto cessò di essere lo scalo esclusivo del grano per Roma.

Economy and society

The economy of Puteoli revolved round the port, which offered good anchorage for large ships. It knew a prolonged golden age, stretching from the 2nd century BC to the 1st century AD. The port of Puteoli played a fundamental role in supplying grain to Rome, and this favoured the city’s whole economy. For the grain trade merchants from Puteoli had established a base on the island of Delos, a strategic port in the Aegean on the route to Egypt, which was a major grain producer. Another commodity available in Delos was slaves, then much in request for agriculture.

The increasingly affluent life style of the Italic aristocracy meant greater demand for luxury goods imported from the Eastern Mediterranean and beyond, from the Indian Ocean to the Red Sea and indeed from the Middle and Far East. Here too the merchants of Puteoli were among the first to exploit the new opportunities. Such trade required high levels of investment at considerable risk, with the prospect of enormous profits, hence the interest of the ruling classes in Rome. It was unseemly in Roman eyes for a senator to be seen to be involved with anything other than the administration of this own lands. Thus they made use of intermediaries such as their own freedmen or important figures in Puteoli society, who would also have invested on their own account. Parallely flourished an entrepreneurial class who embraced all social classes. His factories received the heritage of the Capuan manufacturing traditions. Their products were exported with the same ships which had unloaded at Puteoli. The economy of Puteoli was highly diversified, and this ensured that the city continued to prosper even when the port was no longer the main staging post for grain supplies to Rome.

LA CITTA IN ETÀ TARDOANTICA

Ancora alla fine del IV secolo d.C. il porto era mantenuto in efficienza da ripetuti interventi statali (nn. 13-15). Puteoli riacquisì un ruolo nei confronti di Roma quando Costantino, unico Augusto dal 324 al 337, destinò il grano egiziano all’approvvigionamento di Costantinopoli, inaugurata capitale accanto a Roma l’11 maggio 330. La Campania tornò quindi a fornire una quota importante del grano destinato all’Urbe. Il perdurante decoro urbano è confermato da un gruppo di fiaschette vitree di fine III-IV secolo d.C., con incisa la vista schematica di Puteoli dal mare. Souvenirs per i marinai di ritorno in patria, le raffigurazioni magnificavano l’imponenza delle strutture portuali e degli edifici pubblici. Il declino è invece irreversibile dal V secolo d.C. Nel 410 Roma fu saccheggiata dai Goti guidati da Alarico: conseguenza del sacco fu un drastico calo della sua consistenza demografica, con ripercussioni sui traffici legati al suo approvvigionamento. Le incursioni barbariche in Campania imposero lo spostamento dei traffici superstiti nel porto di Napoli che, a differenza di quello di Puteoli, era protetto dal sistema di fortificazioni della città. Il bradisismo fece il resto.

The city in Late Antiquity

The port was kept in service thanks to a succession of maintenance projects financed by the state, for which there is evidence until the end of the 4th century AD (nn. 13-15). It continued to cater for a substantial volume of traffic, and never ceased to play a part in supplying the Capital. In the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, after a lapse of several centuries, Campania began once again to produce a sizeable part of Rome’s grain supply, now that Egyptian grain was increasingly destined for Constantinople, the Roman Empire’s second capital. We have evidence for the continuing urban splendour of Puteoli in a group of glass flasks dating from the late 3th-4th century AD bearing a schematic depiction of the city from the sea. They were probably intended as souvenirs and the images leave no doubt as to the dimensions of the port facilities and the density and splendour of the public buildings and monuments. By the 5th century AD, however, decline was inevitable. The Goths under King Alaric sacked Rome in 410 and then headed south. Following this onslaught the capital was never again so populous, and this naturally had consequences for the infrastructures guaranteeing its supplies. In any case the incursion of the barbarians into Campania led to most of the remaining traffic being rerouted through the port of Naples, which unlike Puteoli was contained within the city’s system of defences.

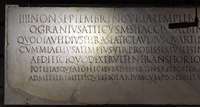

1 Dedica a Lucio Calpurnio Capitolino

Marmo

Inizi I secolo d.C.

Pozzuoli

Inv. 3274 (CIL X, 1797)

“A Lucio Calpurnio Capitolino figlio di Lucio, a Gaio Calpurnio figlio di Lucio, (dedicano) i mercanti che commerciano ad Alessandria, in Asia, in Siria”.

Lucio Calpurnio Capitolino è il munifico cittadino che in età augustea (27 a.C.-14 d.C.) ricostruì, in splendida veste marmorea, il tempio principale della città sul Rione Terra. La dedica attesta il coinvolgimento delle grandi famiglie di Puteoli nei lucrosi traffici marittimi, esercitati soprattutto dai loro liberti residenti sul posto, in Asia (od. Anatolia), in Siria (verso la Persia e l’oriente), ad Alessandria, terminale delle rotte dal Mar Rosso e dall’India.

1 Dedication to Lucius Calpurnius Capitolinus

Marble

Beginning of the 1st century AD.

Puteoli

Inv. 3274 (CIL X, 1797)

“To Lucius Calpurnius Capitolinus, son of Lucius, to Gaius Calpurnius, son of Lucius, (from) the merchants trading in Alexandria, Asia, and Syria”.

Lucius Calpurnius Capitolinus was a munificent citizen of the Augustan age (27 BC -14 AD) who commissioned the rebuilding and splendid marble facing of the main temple of the city, up on the Rione Terra. The dedication bears witness to the engagement of the major families of Puteoli in the remunerative sea trade, practiced especially by freedmen of theirs stationed in Asia (Anatolia), Syria (towards Persia and the Orient), and Alexandria, the terminal of routes from the Red Sea and India.

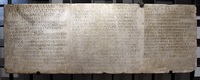

2 Decreto municipale

Marmo

Prima metà del II sec. d.C.

Pozzuoli

Inv. 3278 (CIL X, 1783)

Contiene la relazione di una seduta del senato di Puteoli, circa la richiesta di un cittadino di essere esentato dall’imposta per l’uso del suolo su cui aveva edificato uno stabile nel (Foro) Transitorio (r. 5); in cambio la città avrebbe ereditato “uso, rendita, piena proprietà” dell’edificio: il senato autorizza. La riunione ha luogo nella Curia del templum della Basilica Augusti Anniana (r. 1), nel foro sul Rione Terra, dedicata ad Augusto dalla potente famiglia degli Annii, da tempo attiva nei lucrosi commerci con l’Asia e l’Egitto. La curia è la sede del senato, e la basilica l’edificio dove si amministra la giustizia. Il Foro Transitorio, una piazza legata ad un importante nodo stradale, è stato identificato sul pianoro ad est del Rione Terra (Via Rosini): interventi in età giulio-claudia e soprattutto flavia (relativi alle colonizzazioni di Puteoli successive a quella augustea) lo trasformano in un nuovo centro della città. Il nome “Foro Transitorio” richiama Roma, dove così si chiamava il foro costruito da Domiziano tra l’84 e il 96 d.C.

2 Municipal decree

Marble

First half of the 2nd century AD

Puteoli

Inv.3278 (CIL X 1783)

This slab carries a report about a session of the senate of Puteoli concerning a citizen’s request to be exempted from the tax on the use of the ground on which he had erected a building in the (Forum) Transitorium (line 5); in exchange, the city will grant “use, rent, and full property” of the building. The senate gives its authorization. The meeting took place in the Curia of the templum in the Basilica Augusti Anniana (r. 1), in the town forum on the Rione Terra, dedicated to Augustus by the Annii, a prominent family, long engaged in the lucrative trade with Asia and Egypt. The curia is the senate building, the basilica the building where justice was administered. The Forum Transitorium, a square connected to an important road, is believed to have stood on the plateau east of Rione Terra (Via Rosini). Renovations undertaken in the Julio-Claudian and especially the Flavian periods - at a time when Puteoli’s status as a colony was renewed - transformed this forum into the new city center. The name “Forum Transitorium” was derived from the like-named forum built by Domitian in Rome between AD 84 and 96.

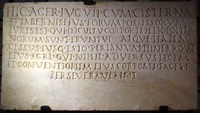

3 Dedica della Colonia Flavia Augusta Puteoli all’imperatore Severo Alessandro

Marmo

226 d.C.

Pozzuoli

Inv. 3261 (CIL X, 1653)

La denominazione Flavia Augusta (r. 9) deriva dalla importante deduzione coloniaria effettuata a Puteoli da Vespasiano (69-79 d.C.): la costruzione del nuovo anfiteatro, fra i maggiori dell’antichità, mostra il decisivo sviluppo demografico ed economico-urbanistico della città nell’età dei Flavi (69-96 d.C.).

I dati onomastici di Severo Alessandro (r. 4, filio; r. 6, Alexandro) sono stati cancellati, come avveniva quando il senato di Roma sanciva la rimozione della memoria di un imperatore.

3 Dedication by the Colonia Flavia Augusta Puteoli to the emperor Severus Alexander

Marble

226 AD.

Puteoli

Inv. 3261 (CIL X, 1653)

The name Flavia Augusta derives from the significant colonial foundation established at Puteoli by the emperor Vespasianus (69-79 AD.). The building of the new amphitheater, one of the largest of antiquity, bears witness to the demographic, economic and urban growth of the city in the Flavian age (69-96 AD.).

The names of Severus Alexander (line 4, filio, line 6, Alexandro) have suffered censure, as was done when the Senate in Rome decreed the erasing of the memory of an emperor.

4 Lapide funeraria di Claudia Aster

Trachite

Ultimo quarto del I secolo d.C.

Pozzuoli

Inv. 4368 (CIL X, 1971)

“Claudia Aster fatta schiava a Gerusalemme. Si incaricò (di porre la lapide) Tiberio Claudio […]colo, liberto di Augusto. Vi prego di fare in modo che nessuno abbatta la lapide contro la legge. Visse venticinque anni”. La defunta, catturata nella sua città di Gerusalemme distrutta da Tito nel 70 d.C., fu probabilmente venduta schiava in Italia a Tiberio Claudio “liberto di Augusto” (si tratta dell’imperatore Claudio, 41-54 d. C.): secondo le regole dell’onomastica degli schiavi, fu chiamata Claudia dal nome del padrone, mentre il suo nome ebraico, Esther, fu traslitterato in Aster.

4 Memorial of Claudia Aster

Trachyte

Late 1st century AD.

Puteoli

Inv. 4368 (CIL X, 1971)

“Claudia Aster, enslaved in Jerusalem. Tiberius Claudius […[culus, freedman of Augustus, saw to (the placing of the tombstone), I beseech you to let no one unlawfully knock down the tombstone. She lived twenty-five years”. The deceased, captured in her city of Jerusalem - destroyed by Titus in AD 70 - was probably sold as a slave in Italy to Tiberius Claudius, “freedman of Augustus” (probably the emperor Claudius, 41-54 AD.) . In conformity with slave naming norms, she was called Claudia from her master’s name. Her Hebrew name, Esther, was transliterated as Aster.

5 Dedica all’imperatore Domiziano

Marmo

93/94 d.C.

Pozzuoli

Inv. 3254 (CIL X, 1631)

La dedica è posta dalla regio del vicus Vestorianus et Calpurnianus, una delle regioni (“rioni”) in cui era divisa Puteoli, e che comprendevano uno o più vici. Tale ordinamento si ispirava al modello adottato da Augusto per Roma. Le regioni fornivano il quadro per vari servizi amministrativi dal censimento al dislocamento dei vigili del fuoco, alla distribuzione dell’acqua, etc. Il nome del vicus deriva dalla presenza di proprietà immobiliari di due famiglie in primo piano nella vita politica ed economica di Puteoli, i Vestori e i Calpurni.

5 Dedication to the emperor Domitian

Marble

93/94 AD.

Puteoli

Inv. 3254 (CIL X, 1631)

This dedication was put up by the region of the vicus Vestorianus et Calpurnianus, one of the neighborhoods’ Puteoli was divided into. Each region included one or more vici. This organization was based on a model introduced by Augustus in Rome. The regions provided various administrative services, from the census to firemen, the water supply, etc. The vicus was named after the Vestori and the Calpurni - two prominent families in the political and economic life of the city - who owned property there.

6 Base di statua dedicata all’imperatore Antonino Pio dal Collegio degli Scabillari

Marmo

139 d.C.

Pozzuoli

Inv. 3255 (CIL X, 1642)

Strumento a lamina vibrante, lo scabillum dava il tempo e segnalava apertura e chiusura del sipario. I collegi erano associazioni professionali autorizzate preventivamente dal senato (r.12: il collegio degli scabillari, cui è lecito riunirsi per decreto del senato), per tema che si trasformassero in strumenti di lotta politica.

Ad Antonino Pio (138-161 d.C.) si devono i restauri del molo e del macellum e l’istituzione degli Eusebeia, giochi quinquennali in onore del padre adottivo Adriano, con la costruzione dello stadio per le gare di atletica.

6 Base of a statue dedicated to emperor Antoninus Pius by the collegium of the scabillari

Marble

139 AD.

Puteoli

Inv. 3255 (CIL X, 1642)

The scabillum was an instrument with a vibrating lamina. It was used to beat out time and signal the drawing and lowering of the curtain. Collegia were professional associations, whose establishment required previous authorization from the senate (line 12: the collegium of the scabillari, who are authorized to congregate by decree of the senate) for fear that they might become instruments in political struggle. Antoninus Pius (138-161 AD.) promoted the restoration of the pier and the macellum and instituted the Eusebeia, quinquennial games in honor of his adoptive father Hadrian, for which a stadium was built to host athletics competitions.

7 Base di statua del pantomimo Lucio Aurelio Pilade

Marmo

Tardo II secolo d.C.

Inv. 121523 (AE 1888 126 = AE 2007 378)

A Pilade, attore di origine greco-orientale più volte vincitore di giochi e onorato a Puteoli con le insegne dei decurioni e dei duoviri, erigono statue gli Augustali della centuria Cornelia (e della centuria Antia: cfr. nn. 9, 10) per la generosità “nell’organizzare uno spettacolo di gladiatori e una venatio passiva (cioè immettendo insieme animali selvaggi di specie diverse), per la benevolenza del sacro principe Commodo Augusto”. Pilade forse ebbe la cittadinanza da Commodo (180-192 d.C.), col cui assenso sembra operare, e il cui nome è in parte cancellato.

7 Base of a statue of the pantomime Lucius Aurelius Pilades

Marble

Late 2nd century AD.

Puteoli

Inv. 121523 (AE 1888 126 = AE 2007 378)

The Augustales of the centuria Cornelia (and the centuria Antia, cf. nos. 9 and 10) erected statues of Pilades, an actor of Eastern Greek origin who had repeatedly won games and was honored in Puteoli with the insignia of the decurions and duoviri, for his generosity “in organizing a gladiator show and a passive venatio (that is, featuring wild animals of different species) for the benevolence of the sacred prince Commodus Augustus”. Pilades may have been granted Roman citizenship by Commodus (180-192 AD.), with whose assent he seems to operate. The name of Commodus is partly erased.

8 Base di statua di Gavia Marciana

Marmo

187 d.C.

Pozzuoli

Inv. 3275 (CIL X 1784)

La dedica celebra lignaggio e virtù della giovane matrona Gavia Marciana, e gli onori funebri decretati dal senato cittadino per la sua prematura scomparsa: funerale pubblico, dieci libbre di essenza profumata, autorizzazione ad erigere tre statue in luoghi della città scelti dalla famiglia. Sul lato destro si registra la riunione di quattro decurioni per verbalizzare le onoranze decise dal senato municipale, tenutasi il 28 ottobre del 187 d.C. nel tempio consacrato dai Puteolani all’imperatore Antonino Pio divinizzato (r. 3; in tempio Divi Pii), per i benefici ricevuti da questo imperatore (cfr. n. 6).

8 Base of a statue of Gavia Marciana

Marble

187 AD.

Puteoli

Inv. 3275 (CIL X 1784)

The dedication celebrates the lineage and virtue of the young matron Gavia Marciana, and the honors granted by the town senate for her premature departure: a public funeral, ten pounds of perfumed essence, and the authorization to erect three statues in town, in spots chosen by the family. On the right side is a registration of the meeting of four decurions to record the honors decreed by the municipal senate. The meeting was held on 28 October, 187 AD., in the temple dedicated by the Puteolani to the deified Antoninus Pius (line 3: in tempio Divi Pii) for the benefits he had granted to them (cf. no. 6).

9 Ara funeraria dell’Augustale A. Arrio Crisanto

Marmo

Tra la prima e la seconda metà del II secolo d.C.

Quarto flegreo, Reginella

Inv. 3385 (CIL X, 1873)

Augustale come Trophimus, Crisanto nel collegio occupava un rango superiore: era duppliciarius (r. 4) con diritto a doppia porzione nei banchetti cultuali e nelle distribuzioni. L’epigrafe conferma che gli Augustali di Puteoli erano divisi in centurie (r. 7: Petronia. Cfr. n. 7). Dobbiamo immaginare che Crisanto, di mestiere marmorarius (r. 2), possedesse una florida officina per la trasformazione del marmo in manufatti artistici ed architettonici. In Italia l’edilizia, sia pubblica che privata, richiedeva enormi quantità di marmi, soprattutto colorati secondo il gusto dell’età imperiale, importati da Grecia, Africa, Egitto, Asia Minore, destinati a Roma, ma anche alle città e alle lussuose ville del Golfo di Napoli.

9 Funerary altar of the Augustalis A. Arrius Chrysanthus

Marble

First-Second half of the 2nd century AD.

Quarto flegreo, Reginella

Inv. 3385 (CIL X, 1873)

Chrysanthus was an augustalis like Trophimus, but held a higher rank in the collegium: he was a duppliciarius (line 4), which means he had a right to a double share in cult banquets and distributions. The inscription confirms that the Augustales of Puteoli were divided into centuriae (cf. no. 7). Chrysanthus was a marbles. In Italy, both the public and the private building industries required huge amounts of marble, especially the colored ones that were fashionable in the imperial period. These were imported from Greece, Africa, Egypt, and Asia Minor to Rome as well as other towns and the luxury villas on the bay of Naples.

10 Cippo coi ritratti di Marco Antonio Trofimo e della moglie

Marmo

Prima età adrianea

Pozzuoli

Inv. 3459 (CIL X, 1872)

Il cippo ornava il sepolcro preparato per sé e la sua famiglia da Trophimus, commerciante in mantelli di lana, membro dei collegi degli Augustali di Puteoli e Neapolis. Composti da liberti facoltosi (lo mostra, nel nostro caso, la qualità dei ritratti) tali collegi, che curavano a proprie spese il culto dell’imperatore, nelle città dell’impero conferiscono un ruolo pubblico a ceti di solida condizione economica e patrimoniale, ma esclusi dall’aristocrazia cittadina, impegnati, al pari di questa, a produrre, commerciare e arricchirsi nei campi più disparati.

10 Cippus with the portraits of Marcus Antonius Trophimus and his wife

Marble

First Hadrian Age

Puteoli

Inv. 3459 (CIL X, 1872)

The cippus graced the tomb prepared for himself and his family by Trophimus, a woolen-cloak merchant and a member of the collegia of Augustales of Puteoli and Neapolis. These collegia, which performed the cult of the emperor at their own expense, gathered rich freedmen, and this is reflected in the quality of the portraits on the cippus. In the towns of the Empire, these collegia granted a public role to members of rich classes who were excluded from the town aristocracy. Like the aristocrats, they were engaged in trading and making money in a variety of ways, including many flourishing manufacturing trades.

11 Legge municipale (lex parieti faciendo)

Marmo

Copia di prima età imperiale dell’originale del 105 a.C.

Pozzuoli

Inv. 3231 (CIL X, 1781)

Si tratta di un dettagliatissimo capitolato d’appalto, con triplice datazione (anno dalla fondazione della colonia; nomi dei duoviri locali, nomi dei consoli di Roma: col. 1, rr. 2. 3): 105 a.C. della nostra cronologia. Il testo è intitolato “seconda legge sulle opere” (col. 1, r. 4). Si è perciò ipotizzato che esso faccia parte di un più ampio capitolato relativo alla costruzione di un tempio di Honos (col. 2, rr. 10, 11). Il testo conservato riguarda la recinzione, con l’apertura di una porta su strada, e la liberazione da preesistenti strutture (edicole, altari, statue, col. 3, r. 2), di un’area “di fronte al tempio di Serapide, al di là della strada” (col. 1, rr.5, 6). Indizi consistenti situano questi edifici fuori dal nucleo originario di Rione Terra, nella zona del porto commerciale. Serapide era il dio nazionale egiziano, e questa attestazione, la più antica in Italia del suo culto, fa pensare ad una presenza stanziale di mercanti di Alessandria a Puteoli. Nelle adiacenze del tempio di Serapide, si trovava dunque quello di Honos, divinità romana fortemente connotata in senso trionfale (honos significa anche “onore militare” e “giusta ricompensa per la vittoria”). Il 105 a.C., a cui risale l’appalto, è l’anno della vittoria di Gaio Mario su Giugurta, re di Numidia (attuale Tunisia), in una guerra fortemente voluta dai ceti mercantili romano-italici, dei cui ingenti interessi mediterranei Mario era il campione, e che comprendevano le più cospicue famiglie di Puteoli.

11 Municipal act (lex parieti faciendo)

Marble

Early imperial age reproduction from the original of 105 BC.

Puteoli

Inv. 3231 (CIL X, 1781)

The inscription consists of very detailed tender specifications for building works, bearing a triple date: by year from the foundation of the colony, by the names of the local duoviri, and by the names of the consuls of Rome (col. 1, lines 2, 3). In our calendar, this year corresponds to 105 BC. The text is entitled “second act about works” (col. 1, line 4). It may hence have been part of a longer tender document relative to the building of a temple of Honos (col. 2, lines 10, 11). The preserved text concerns the enclosure wall. It refers to the opening of a door onto the street and the freeing up from preexisting structures (aedicules, altars, and statues, col. 3, line 2) of an “area in front of the temple of Serapis, beyond the street” (col. 1, lines 5, 6). There is substantial evidence that these buildings stood outside the old town limits of Rione Terra, in the area of the commercial port. Serapis was the Egyptian national god and this inscription, providing the earliest evidence of his cult in Italy, is suggestive of permanent residence of merchants from Alexandria in Puteoli. So near the temple of Serapis there was one dedicated to Honos, a Roman deity with strong triumphal connotations, since honos means also: “military honor” and “rightful reward for victory”. The year AD 105, when the works were commissioned, is the year of Gaius Marius’ victory over Jugurtha, king of Numidia (present-day Tunisia). This war had been strongly solicited by the Roman-Italic mercantile class, which included some of Puteoli’s most prominent families. Marius was the champion of the conspicuous Mediterranean interests of this class.

12 Altare sacro a Dusares

Marmo

I secolo d.C.

Pozzuoli, presso il Macellum

Inv. 3248 (CIL X, 1556)

Dusares, divinità della forza vitale che pervade la natura, era il dio nazionale degli Arabi Nabatei, stanziati nell’Arabia settentrionale e affacciati sul Mar Rosso, in posizione strategica lungo la via delle merci di lusso, che dall’Oceano Indiano, attraverso il Mar Rosso e le vie carovaniere, erano dirette ad Alessandria d’Egitto.

I Nabatei sono precocemente presenti a Puteoli, dove edificano nel 50/49 a.C. un santuario (marahmta) restaurato nel 5 d.C. A parte forse gli Alessandrini, costituiscono la più antica comunità mercantile straniera residente sicuramente attestata a Pozzuoli.

12 Altar sacred to Dusares

Marble

1st century AD.

Puteoli, near the Macellum

Inv. 3248 (CIL X, 1556)

A deity of the vital force pervading nature, Dusares was the national god of the Nabatean Arabs, who resided in northern Arabia along the Red Sea coast, in a strategic position on the route by which luxury goods from the Indian Ocean arrived to Alexandria in Egypt through the Red Sea and caravan ways. Nabateans took residence in Puteoli early on. In 50/49 BC. they built a sanctuary (marahmta) here, which was restored in 5 AD. With the possible exception of the Alexandrines, they are the earliest foreign resident community attested in Puteoli.

13-14-15 Tre iscrizioni commemoranti il rifacimento della banchina portuale

Marmo

394/395 d.C.

Pozzuoli, Macellum

Invv. 3266; 3267; 3265 (CIL X 1690;1691;1692)

13: “Per la felicità dei nostri signori ed Augusti, Valerio Ermonio Massimo, uomo nobilissimo, governatore della Campania, iniziò e condusse a termine i lavori per la banchina dalla parte sinistra del mercato alimentare (macellum), provvedendo anche ad alzare argini contro la violenza dei marosi”.

14: Epigrafe gemella del n. 13, relativa alla banchina dalla parte destra del mercato alimentare (macellum).

15: “Per la beatitudine della nostra epoca, per la felicità dello Stato e degli imperatori nostri signori Teodosio, Arcadio e Onorio per sempre Augusti. La banchina a destra e a sinistra del mercato, costruita al fine di garantire favore e splendore a Puteoli, inaugurò Fabio Pasifilo, uomo nobilissimo, facente funzioni di prefetto del pretorio e di prefetto di Roma”.

Come attestano i nn. 13 e 14, nel 394/395 d.C. le banchine a sinistra a destra del macellum vengono restaurate e protette con argini dai marosi a cura del governatore della Campania; l’opera è inaugurata (n. 15) dal plenipotenziario degli imperatori, che cumulava ad interim le altissime funzioni di prefetto del pretorio e prefetto di Roma. Ciò attesta la perdurante vitalità del porto di Puteoli e l’interesse dei vertici dell’impero per il suo buon funzionamento. Il macellum era il mercato alimentare nella zona del porto. noto oggi come “Tempio di Serapide” per il ritrovamento di una statua del dio collocata nell’abside di fondo.

13-14-15 Three inscriptions on marble commemorating the renovation of the quay

Marble

394/395

Puteoli, Macellum

Invv. 3266; 3267; 3265, (CIL X 1690; 1691; 1692)

13: “For the joy of our lords and Augusti, Valerius Hermonius Maximus, a most distinguished man, governor of Campania, started and brought to completion work on the quay on the left side of the food market (macellum), also taking care to erect embankments against the violence of the sea”.

14: Twin epigraph of no. 13, relative to the wharf on the right side of the food market (macellum).

15: “For the beatitude of our time, for the happiness of the State and the emperors, our lords, Theodosius, Arcadius and Honorius, forever Augusti. Fabius Pasiphilus, a most distinguished man, acting as prefect of the praetorium and prefect of Rome, inaugurated the quay on the right and left side of the market, built to grant favor and splendor to Puteoli”. As documented by nos. 13 and 14, in AD 394/395 the wharves left and right of the macellum were restored and protected with banks against the waves at the behest of the governor of Campania. This work was inaugurated (no. 15) by the plenipotentiary of the emperors, who temporarily combined the high offices of prefect of the praetorium and prefect of Rome. This attests to the enduring vitality of the port of Puteoli and the interest of the higher echelons of the Empire in its efficiency. The macellum was the food market in the port area. It is known today as “Temple of Serapis” for the discovery of a statue of this god in the apse at the back of the building.

16 Base di statua dedicata a Mavorzio Iunior

Marmo

Prima metà del IV secolo d.C.

Pozzuoli (1704)

Inv. 3264 (CIL X, 1697)

“Di Mavorzio Iuniore. A Quinto Flavio Mesio Cornelio Egnazio Severo Lolliano, fanciullo nobilissimo, candidato alla questura, i decatrensi suoi clienti al validissimo patrono”. Il giovanissimo figlio di Mavorzio (n. 21) riceve, quale patrono, l’onore di una statua: le comunità clienti radicavano durevolmente il patronato di famiglie da cui ricevevano protezione. La statua è posta dai Decatrenses (r. 5), abitanti della regio decatriae (“Il quartiere della decatria”, termine di discusso significato). I Decatrenses potrebbero essere, più specificamente, membri del “collegio dei Decatrensi” (probabilmente un’associazione con scopi cultuali), che dedica una statua al padre.

16 Base of a statue dedicated to Mavortius Iunior

Marble

First half of the 4th century AD.

Puteoli (1704)

Inv. 3264 (CIL X, 1697)

“Of Mavortius Iunior. To Quintus Flavius Mesius Cornelius Egnatius Severus Lollianus, a most distinguished youth, candidate to the quaestorship, the Decatrenses, his clients, to their most worthy patron”. The young son of Mavortius (see no. 21), whose nickname he shares, is thus honored with a statue in thanks for his patronage. Communities of clients maintained long-lasting loyalties to the families they received protection from. The statue was erected by the Decatrenses (line 5), that is, the inhabitants of the regio decatriae (a term whose meaning is debated), or members of the “collegium of Decatrenses”, (perhaps a confraternity), who dedicated a statue to Mavortius Senior.

17 Dedica bilingue al “dio santo” di Tiro

Marmo

I secolo d.C.

Pozzuoli, via Celle

Inv. 2425 (CIL X, 1601)

“Sacerdote Siliginio / Tiro metropoli] / fede[rata] (in latino) / Tiro sacra inviolabile… [metro] /poli della Fenicia…/delle\tra le città /Al dio santo venerabile (?)… (in greco)”. La scritta sulla cornice è posteriore: Siliginio, se non è il cognome del sacerdote, potrebbe significare “che offre farina pura (siligo)” alla divinità. Tiro (in Libano) era antichissima e attivissima città fenicia celebre per la produzione della porpora; foederata (“che ha stipulato un trattato bilaterale”) con Roma, aveva stazioni commerciali nell’Urbe e a Puteoli. Nel “dio santo”, non nominato, come voleva la religione fenicia, si riconosce generalmente Baal-Melqart, divinità suprema assieme fecondatrice e distruttrice, presente nei più possenti fenomeni della natura. Si è proposto anche Eshmun, dio taumaturgo, assimilabile ad Asclepio/Esculapio.

17 Dedication to the “holy god” of Tyre

Marble

1st century AD.

Puteoli, via Celle

Inv. 2425 (CIL X, 1601)

<è>“Priest Siliginius. Tyre, fede[rated] m[etropolis] (in Latin) Tyre, sacred, inviolable… [metro]polis of Phoenicia… of/among the cities… to the holy venerable (?) god (in Greek)”. “Priest Siliginius” is later. Unless it is the cognomen (last name) of the priest, Siliginius may mean “he who offers pure flour (siligo)” to the god. Tyre in Lebanon was an ancient and very active Phoenician city, renowned for the production of purple dye. An ally (foederata) of Rome, it had commercial outposts in Rome and Puteoli. The “holy god” in question -whose name is not uttered, as Phoenician religion prescribed - is Baal-Melqart, a supreme deity, at once a creator and a destroyer, present in the most powerful natural phenomena. According to an other conjecture, the “holy god” could be Eshmun, thaumaturgical deity, assimilabile with Asclepios/ Aesculapius.

18 Una proprietà degli Eliopolitani

Marmo

II secolo d.C.

Pozzuoli

Inv. 3246 (CIL X, 1579)

“Questo campo di sette iugeri, con una cisterna e ambienti di servizio di sua pertinenza, è di proprietà di coloro che osservano e osserveranno le norme dell’associazione (corpus) degli Eliopolitani. Abbiano diritto all’accesso per le porte e i sentieri di questo campo coloro che non hanno mai trasgredito la legge e gli accordi di questa associazione”. L’associazione di cittadini di Eliopoli in Siria, fedeli del culto patrio di Giove Eliopolitano, possiede in piena proprietà (vedi la formula eorum possessorum iuris est rr. 2, 3) un appezzamento di circa ettari 1.50, forse usato come cimitero.

18 A property of the Heliopolitans

Marble

2nd century AD.

Puteoli

Inv. 3246 (CIL X, 1579)

“This seven-iugerum field, with the cistern and service rooms that go with it, is the property of those who follow and will follow the rules of the association (corpus) of the Heliopolitans. Let those have access to the gates and paths of this field who have never broken the law or agreements of this association”. The association of the citizens of Heliopolis in Syria, worshipers of their national god Jupiter Heliopolitanus, has full property rights (as specified by the formula eorum possessorum iuris est. lines 2, 3) of a plot of about 1.50 hectares, possibly used as a burial ground.

19 Onori degli Eliopolitani al sacerdote Aurelio Teodoro

Marmo

II secolo d.C.

Pozzuoli

Inv. 3236 (CIL X, 1578)

“Per ordine di Giove Ottimo Massimo Eliopolitano, i sacerdoti e gli zigofori… posero a proprie spese una ghirlanda e un velo in onore di Aurelio Teodoro figlio, sacerdote, curatore del tempio dei Geremellensi, da lui ampliato con doni”.

Giove Eliopolitano è frutto di un sincretismo tra il dio supremo dell’Olimpo greco-romano e Hadad il dio siriano di Baalbek - in età ellenistica denominata Heliopolis (“città del sole”). I Geremellensi (termine di significato incerto) erano forse un’associazione di fedeli che prendeva nome dalla comunità di origine (n. 18). Gli “zigofori” (o “iugofori”; r. 7), letteralmente “portatori del giogo”, forse assistevano i sacerdoti nei riti e nelle processioni, conducendo i tori che fiancheggiavano il dio.

19 A homage of the Heliopolitans to the priest Aurelius Theodorus

Marble

2nd century AD.

Puteoli

Inv. 3236 (CIL X, 1578)

“By order of Jupiter Optimus Maximus Heliopolitanus, the priests and zygophori… offered at their own expense a wreath and a veil in honor of Aurelius Theodorus junior, priest, curator of the temple of the Geremellenes, which he expanded through his donations”. Jupiter Heliopolitanus is the result of the syncretic merging of the supreme god of the Greek-Roman pantheon and Hadad, the Syrian god of the town of Baalbek, called Heliopolis (“city of the sun”) in the Hellenistic period. The Geremellenes (a term of uncertain meaning) were possibly an association of devotees named after their community of origin (no. 18).The “zygophori” (or “iugophori”; line 7), literally “yoke carriers”, possibly assisted priests in rites and processions by leading forth the bulls that walked alongside the god.

20 Base di statua in onore di Marcus Nemonius Eutychianus

Marmo

Metà del II secolo d.C.

Bacoli, Miseno

Inv. 3237 (CIL X, 1576)

La statua è dedicata al collega Marco Nemonio Eutichiano dai sacerdoti di Giove Damasceno Ottimo Massimo, divinità in cui si riconosce la divinità suprema siriaca Hadad, qui venerata come Giove di Damasco, importante città carovaniera siriana.

Il cognome grecanico del personaggio onorato sembra denotarne una discendenza libertina piuttosto che un’origine orientale, che non gli ha impedito l’ascesa all’ordine equestre (e viene sottolineato come il conferimento si debba all’imperatore Antonino Pio) e, a Puteoli, l’accesso al senato municipale e il conseguimento della edilità.

20 Statue base in honor of Marcus Nemonius Eutychianus

Marble

Half of the 2nd century AD.

Bacoli, Miseno

Inv. 3237 (CIL X, 1576)

The statue is dedicated to their colleague Marcus Nemonius Eutychianus by the priests of Jupiter Damascenus Optimus Maximus, a deity identified with the supreme Syrian god Hadad, worshiped here as Jupiter of Damascus, an important Syrian caravan city.

The Greek cognomen (last name) of the honored personage appears to denote freedman origin rather than oriental origin. This did not prevent his rise to the rank of a Roman knight (which he owes to Antoninus Pius, as pointed out here) and, in Puteoli, his becoming a member of the town senate and an aedile.

21 Base di statua di Mavorzio (336/7 - 342 d. C.). Sul retro, precedente dedica all’imperatore Carino (283-285 d.C.)

Marmo

Pozzuoli, via Rosini

Inv. 3263 (CIL X, 1695)

“(Statua) di Mavorzio. A Quinto Flavio Mesio Egnazio Lolliano [seguono le tappe della camera] il quartiere di Porta Trionfale al patrono degnissimo”.

Egnatius Lollianus soprannominato Mavortius (da Mavors, forma arcaica per Mars, Marte), prestigioso esponente dell’aristocrazia romana, raggiunse i vertici dell’amministrazione imperiale; ma nella nostra epigrafe si ferma al governo dell’Africa (336/337 d.C.). A lui, come patrono della colonia, erigono statue almeno quattro regiones di Puteoli (nn. 5, 16); la regio Portae Triumphalis, forse aperta sul Foro Transitorio (n. 2), riecheggiava nel nome la toponomastica di Roma.

21 Base of a statue of Mavortius (336/7 - 342 AD.). On the back there is an earlier dedication to the emperor Carinus (283-285 AD)

Marble

Puteoli, via Rosin

Inv. 3263 (CIL X, 1695)

“(Statue) of Mavortius. To Quintus Flavius Mesius Egnatius Lollianus [followed by the stages in his career], The neighborhood of Porta Triumphalis to its most worthy patron”.

Egnatius Lollianus, nicknamed Mavortius (from Mavors, an archaic form of the name of the god Mars), a prestigious exponent of the Roman aristocracy, rose to the highest ranks of the imperial administration. The inscription, however, goes no further than his governorship of Africa (AD 336/337). At least four regions of Puteoli erected statues to him as a patron of the colony (nos. 5, 16). The name of the regio Portae Triumphalis, which possibly looked onto the Forum Transitorium (no. 2) echoed that of a like-named monument in Rome.

22 Anfora da trasporto (Dressel 2-4 di produzione italica)

70 a.C.- II secolo d.C.

Pozzuoli

In età romana, questi contenitori erano impiegati per il trasporto del vino sulla spalla e presente il titulus pictus tracciato a grandi pennellate di colore nero e lacunoso: MA-R.

22 Freight amphora (Dressel 2-4, made in Italy)

70 BC-2nd century AD

Pozzuoli

In the Roman age, these containers were used to transport wine. On the shoulder is the following titulus pictus traced in broad, black and broken brushstrokes: MA-R.

23 Anfora da trasporto (Dressel 2-4 di produzione tarraconense)

Eta tiberiana - inizi II secolo d.C.

Pozzuoli

Questo contenitore , prodotto probabilmente sulla costa catalana) era riservato al trasporto del vino. Sul fondo è ben leggibile il bollo AT in cartiglio circolare, forse cognomen di valenza etnica (Atticus?) che ricorre nei prodotti dell’Hispania.

23 Freight amphora (Dressel 2-4, made in Tarracona)

Tiberian age (early 2nd century AD)

Pozzuoli

This container, probably manufactured on the Catalan coast, was used to transport wine. On the bottom, the stamp AT is well readable in a round cartouche. It is possibly an ethnic cognomen (Atticus?), commonly found on products from Hispania.

24 Anfora da trasporto (Chalk 6, Peacock-Williams Class 50, Augst 53)

Pozzuoli

La morfologia generale dell’anfora rimanda ad una serie di anfore rare datate tra il III e il IV secolo d.C. Si tratta di un contenitore d’incerta produzione, recante sul collo tracce del titulus pictus di colore rosso, molto lacunoso e di difficile interpretazione.

24 Freight amphora (Chalk 6, Peacock-Williams Class 50, Augst 53)

Pozzuoli

The general shape of the vessel is akin to that of a group of rare amphorae dated between the 3rd and 4th century AD. We do not know where this vase was made. On the neck are traces of the titulus pictus, painted in red. It is badly preserved and hence hard to decipher.

Le tre anfore - The three amphorae

Fotografie di Giorgio Manusakis