LA VITA SUI MURI

I muri di Pompei - facciate e pareti interne di edifici pubblici, privati, religiosi, persino funerari - erano coperti da scritte, dipinte o graffite, di contenuto disparatissimo: propaganda elettorale, offerte commerciali, annunci di spettacoli teatrali e gladiatori, saluti, complimenti, ingiurie, lamentele, sospiri di amore, fantasie erotiche, oscenità; e ancora, annunci di nascita e di morte, conti, elenchi di oggetti. Scritture prodotte da molti e rivolti a molti, appartenenti a tutti gli strati sociali, che testimoniano il livello di alfabetizzazione raggiunto a Pompei, e quindi nel mondo romano, nei primi secoli dell’impero.

I testi sono frutto di abilità scrittorie, grammaticali ed espressive differenti. Le scritte a pennello sono, in genere, di tipo pubblicitario e seguono uno schema più o meno fisso; i graffiti, invece, variano enormemente per contenuto e registro linguistico.

Mani ignote graffiano i muri per dare forma ad uno stato d’animo o a pensieri occasionali affidati a citazioni letterarie o a sciatte espressioni che cedono spesso al turpiloquio. Le affermazioni di alcuni provocano la risposta di altri. Le frasi si affastellano per il concorso di mani diverse. Sono segni disarticolati che ignorano il rigore formale delle iscrizioni pubbliche e che spesso violano le regole della grammatica, ma che restituiscono in tutta concretezza la vita delle persone.

Life on the walls

The walls of Pompeii - facades and inside walls of public, private, religious, and even funerary buildings - were covered by painted or scratched writings of very varied content: electioneering, commercial offers, announcements of theatre and gladiator shows, greetings, congratulations, insults, complaints, sighs of love, erotic fantasies, obscenities, announcements of birth and death, accounts, lists of objects.

Writings produced by many people and aimed at many people, from all social strata, which testify the level of literacy achieved in Pompeii, and generally in the Roman world, in the first centuries of the empire.

The texts are the result of a wide range of writing, grammar, and expressive skills. Those written by brush are, in general, of advertising type and follow a more or less fixed pattern; graffiti, however, vary greatly in content and language register.

Unknown hands scratched the walls to give shape to a mood or passing thoughts, entrusted to literary quotations or sloppy expressions that often succumb to bad language. The statements of some provoke responses from others. Different hands pile sentences on sentences. These are disjointed signs that bypass the formal rigor of public notices and often violate the rules of grammar, but that reflect people’s lives thoroughly.

CHE PASSIONE LA CAMPAGNA ELETTORALE

A Pompei, come in ogni altra città del mondo romano, il momento più importante della vita pubblica era rappresentato dall’elezione annuale dei magistrati municipali, i duoviri e gli aedilies. La propaganda dei candidati avveniva anche con “manifestii elettorali” (programmata) dipinti sulle pareti esterne degli edifici, in cui non era il candidato a chiedere il voto ma i suoi sostenitori (rogatores).

Questi manifesti erano dipinti a lettere capitali col minio rosso o nero su un leggero strato d’intonaco umido o su una velatura di calce diluita. Erano ovviamente preferiti gli edifici collocati nelle strade principali e nelle zone più frequentate.

A scrivere erano professionisti, gli scriptores, che durante l’anno si guadagnavano da vivere dipingendo manifesti di altro genere, annunci di feste e spettacoli, vendite, locazioni. Essi operavano ad lunam, di notte, da soli, o più spesso in piccole squadre con precisa divisione dei compiti. Particolare cura era messa nel tracciare il nome del candidato a lettere più grandi e vistose delle altre. Seguiva l’indicazione della carica politica e la richiesta del voto. Questa è espressa sotto forma di preghiera con la sigla OVF, tre lettere solitamente unite in un unico nesso e che si sciolgono in oro vos faciatis «vi prego di fare», cioè di eleggere.

Forme abbreviate sono in uso anche per l’indicazione della carica politica al caso accusativo: IIvir o IIvir i d (duovirum o duumvirum oppure duovirum o duumvirum iure dicundo); aed (aedilem); quinq (quinquennalem) . Un’altra abbreviazione ricorrente è la menzione di merito del candidato DRP (dignum rei publicae «meritevole di amministrare la cosa pubblica»).

La maggior parte delle iscrizioni è relativa agli ultimi anni di vita della città, poiché questi documenti dovevano durare per il breve tempo richiesto dalla competizione elettorale; poi venivano cancellati con una mano di vernice per far posto a nuovi annunci.

Tuttavia non mancano, per varie ragioni, esempi più antichi che risalgono fino alla fondazione della colonia sillana (80 a.C.).

The passion for the election campaign

In Pompeii, as in every city of the Roman world, the most important moment in public life was represented by the annual election of municipal magistrates, duoviri and aediles.

Candidates’ propaganda also took the form of electoral posters (programmata) painted on exterior walls of buildings, on which the candidate’s supporters (rogatores), not the candidate, asked for people’s vote.

These posters were painted in capital letters with black or red minium on a light layer of wet plaster or on a glazing of diluted lime. The buildings located in the main streets and in the busier areas were of course the most favoured. The writers were professionals, the scriptores, who made a living by painting other kinds of posters during the year: announcements of feasts and shows, sales, leases. They operated ad lunam, by night, alone, or more often in small teams with clear division of tasks. Particular care was required in tracing the name of the candidate in larger and more conspicuous letters than the rest. There followed the indication of the political office sought and the request for a vote.

This is expressed in the form of a prayer with the acronym OVF, three letters usually combined into a single symbol, and that mean: “Oro Vos Faciatis”, “I beg you to elect the candidate”. Abbreviated forms were also in use for the indication of political office in the accusative case: IIvir (duovirum or duumvirum), or IIvir i d (duovirum or duumvirum iure dicundo); aed (aedilem); quinq (quinquennalem).

Another recurring abbreviation concerns the suitability of the candidate to the office: DPR (dignum rei publicae “worthy of administering public affairs”).

Most of the inscriptions refer to the final years of the city’s life, because these writings were supposed to last for the short time required by the electoral competition. They were then covered with a coat of paint to make way for new posters. However, for various reasons, there are older examples dating back to the founding of the colony by Silla (80 BC).

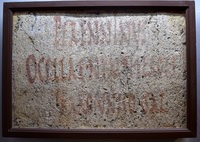

A CASA DI GIULIA FELICE

17 anni dopo il terremoto che aveva colpito la Campania nel 62 d.C. molte case di Pompei risultavano ancora inagibili o in corso di restauro. Per far fronte alla crisi degli alloggi, una donna animata da spirito imprenditoriale ricavò nella propria lussuosa abitazione lotti da affittare separatamente.

in praedis iuliae sp. f. felicis

locantur

balneum venerium et nongentum tabernae

pergulae

cenacula ex idibus aug primis in idus aug sextas

annos continuos quinque

s. q. d. 1. e. n. e.

Nella proprietà di Giulia Felice, figlia di Spurio si affittano un bagno elegante per persone di rango, botteghe con l’abitazione soprastante, appartamenti al primo piano, dalle prime Idi di agosto alle seste Idi di agosto, per cinque anni consecutivi.

Alla fine del quinquennio la locazione sarà rinnovata con semplice consenso. (?)

L’avviso di locazione elenca accuratamente i locali in offerta. Sono indicate la data di inizio e scadenza, la durata e, con sigle, le modalità della stipula o della proroga del contratto, che allo scadere del cinquennio sarebbe stato rinnovato con un semplice accordo (si quinquennium decurrerit locatio erit nudo consensu, secondo la proposta di scioglimento della sigla avanzata da Giuseppe Fiorelli ma non condivisa da tutti gli studiosi).

Discussa è l’interpretazione dell’espressione balneum venerium et nongentum con la quale si intendeva sottolineare che l’impianto termale era così raffinato da essere degno di cittadini di riguardo quali erano i nongenti, ovvero i guardiani delle urne elettorali, e i venerii, i giovani aristocratici della locale associazione sacra a Venere. Venerium come aggettivo di Venere viene inteso da alcuni studiosi col significato generico di “bello” o”elegante”; da altri come allusivo ai piaceri erotici garantiti da Venere e quindi come esplicito riferimento all’esercizio della prostituzione, che si poteva praticare negli ambienti annessi alle terme.

L’insegna scritta a grandi lettere nere su un preciso tracciato di linee nere doveva risaltare accanto all’ingresso monumentale aperto su via dell’Abbondanza.

Accanto all’avviso di locazione si disponevano disordinatamente manifesti elettorati con i nomi dei candidati all’edilità esaltati per le loro buone qualità.

Giulia Felice’s house

17 years after the earthquake that struck Campania in 62 A.D., many of Pompeii’s houses were still uninhabitable or undergoing restoration. To cope with the housing crisis, a woman animated by an entrepreneurial spirit divided her luxurious home in order to get lots to rent separately.

in praedis iuliae sp. f. felicis

locantur

balneum venerium et nongentum tabernae

pergulae

cenacula ex idibus aug primis inidus aug sextas

continuos annos quinque

s.q. d. 1. e. n. c.

In the property of Giulia Felice, daughter of Spurius there are for rent a stylish bathroom for people of rank, workshops with overlying housing, first floor apartments, from the first Ides of August at the sixth Ides of August, for five consecutive years.

At the end of the five years the lease will be renewed with simple consent. (?)

The lease notice carefully lists the properties on offer. Specifying the date of the start and expiry dates, duration and, with acronym, the methods for making or extending the contract, which on termination of the five years would be renewed with a simple agreement (si quinquennium decurrerit locatio erit nudo consensu, according to the solution advanced by Giuseppe Fiorelli but not shared by all scholars). Scholars debate also the interpretation of the expression balneum venerium et nongentum, which was intended to emphasize that thermae were so refined as to be worthy of respectable citizens as were the nongenti, the guardians of the ballot boxes, and the venerii, young aristocrats from the local association sacred to Venus. “Venerium”, as adjective from “Venus”, is understood by some scholars to have the general meaning of “beautiful” or “elegant”; by others as alluding to erotic pleasures guaranteed by Venus and then as an explicit reference to the exercise of prostitution, which was allowed in the annexes of the thermae.

The sign, written in large black letters on a precise pattern of black lines, must have stood out next to the monumental entrance on Via dell’Abbondanza.

Next to the lease notice, electoral posters were disorderly arranged, with the names of candidates for the office of aeailis, exalted for their good qualities.

POETI DI STRADA

Tra i graffiti che ricoprono i muri di Pompei molti sono in versi.

Ci sono brevi componimenti originali sul tema della sofferenza d’amore, ispirati dall’elegia latina di età augustea, rappresentata da Ovidio, Tibullo, Properzio.

Troviamo anche citazioni letterali o libere, soprattutto da Ovidio e Properzio.

È interessante che queste citazioni sono organizzate autonomamente dallo scrivente, per produrre messaggi personali. Così, il distico n. 23 unisce in un testo unitario una citazione libera da Properzio e una letterale da Orazio.

In un altro caso, tre distici originariamente distinti - due di Ovidio, uno di Properzio - sono incolonnati dalla stessa mano, per lamentare l’inaccessibilità della donna amata, e contrapporvi l’ostinazione alla lunga vincente dell’amante respinto.

Non si contano i casi in cui il verso è al servizio dell’oscenità. Qui gli scriventi mostrano familiarità con i versi adoperati nel teatro comico, nella poesia d’invettiva, nella poesia oscena nota come “Canti di Priapo” (dio della fertilità, dall’enorme fallo sempre eretto, benaugurante ed efficace contro il malocchio).

Ma poi non mancano massime di saggezza, che forse riecheggiano quel filone della commedia antica che aveva fini di edificazione morale, rappresentata dal greco Menandro e dal romano Terenzio. Il verso serviva anche per fare satira, sui muri, dell’ossessionante presenza, sui muri, della propaganda elettorale: «Mi meraviglio, o muro, che tu non sia crollato sotto il peso di tanti noiosi manifesti elettorali». (Trad. di Marcello Gigante).

Street poets

Among the graffiti covering the walls of Pompeii, many are in verse.

There are short original compositions on the theme of heartbreak, inspired to Latin elegy of the Augustan age, represented by Ovid, Tibullus, Propertius.

We also find literal or free quotes, mostly by Ovid and Propertius. It’s interesting that these quotes are organized with autonomy by the writer, to produce personal messages.

Thus, a couplet (n. 23) combines in a single text a free quote from Propertius and a literal one by Horace.

In a different case, three couplets originally distinct - two by Ovid, one by Propertius - are lined up by the same hand, to complain about the inaccessibility of his beloved, contrasting it with the eventually successful determination of the long rejected lover.

There are countless cases where the verse is at the service of obscenity.

Here the writers show familiarity with the verses used in comic theater, in invective poetry, in obscene poetry known as “Songs of Priapus” (god of fertility, with an enormous ever-erect phallus, auspicious and effective against bad luck). But then there is no shortage of learned aphorisms, perhaps echoing that line of ancient comedy that had the purpose of moral edification, represented by the Greek Menander and the Roman Terence.

The verse also served as a tool of satire, on the walls, about the obsessive presence, on the walls, of electioneering: “I am astonished, oh wall, that you haven’t collapsed under the weight of so many boring election posters”. (Trad. M. Gigante).

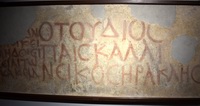

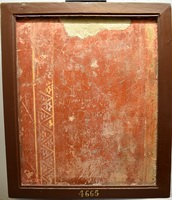

1 Frammento di intonaco dipinto

Testo in lingua greca, lettere dipinte in rosso

Pompei, VIII 4, 7, sulla parete destra della taverna di Severus

Inv. 4717

“Qui abita il figlio di Zeus, Eracle glorioso vincitore; non entri il male”

1 Fragment of painted plaster

Greek text, red letters

Pompeii, VIII 4, 7, right wall of the tavern of Severus

Inv. 4717

“Here dwells the son of Zeus, Heracles the glorious victor; may evil keep out”.

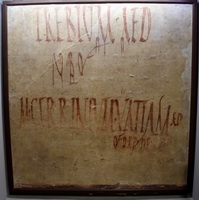

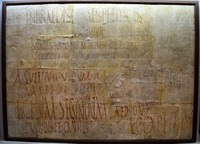

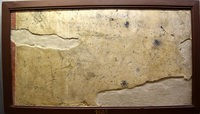

2 Frammento di intonaco dipinto

Lettere dipinte in rosso

Età flavia

Pompei, via Consolare nelle vicinanze delle botteghe VI 17, 7 e 8

Inv. 4673

A. “Votate Trebio, onest’uomo, come edile”

B. “Votate Marco Cerrinio Vatia come edile, meritevole della pubblica amministrazione. Iarino (raccomanda)”

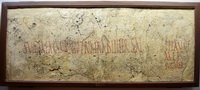

2 Fragment of painted plaster

Red letters

Flavian age

Pompeii, Via Consolare, near shops VI 17, 7, and 8

Inv. 4673

A. “Vote for Trebius, an honest man, for aedile”

B. “Vote for Marcus Cerrinius Vatia for aedile, who is worthy of public office. Iarinus (recommends him)”.

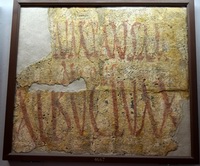

3 Frammento di intonaco dipinto

Lettere dipinte in rosso

Età flavia (79 d.C.?)

Pompei, II 4,1 ad ovest dell’entrata 1

Inv. 4667

<strong<a.< b=""> “Votate Cuspio Pansa come edile”B. “Votate Albucio come edile”

3 Fragment of painted plaster

<p

Flavian age (AD 79?)

Pompeii, II 4, 1, west of entrance 1

Inv. 4667

<strong<a.< b=""> “Vote for Cuspius Pansa for aedile”

B. “Vote for Albucius for aedile”

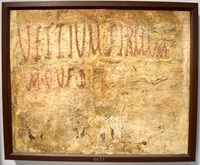

4 Frammento di intonaco dipinto

Lettere dipinte in rosso

Età flavia

Pompei, II 3, parte settentrionale dell’insula

Inv. 4674

“Votate Vettio Firmo come edile degno di essere pubblico amministratore”

4 Fragment of painted plaster

Red letters

Flavian age

Pompeii, II 3, northern part of the insula

Inv. 4674

“Vote for Vettius Firmus for aedife, (who is) worthy of being a public administrator”

5 Frammento di intonaco dipinto

Lettere dipinte in nero

Età giulio-claudia o flavia

Pompei, II 4, 6 facciata nord del complesso del praedia di Giulia Felice

Inv. 4713

B. “Votate Aulo Vettio Vero come edile addetto alle strade e agli edifici sacri e pubblici, meritevole della pubblica amministrazione, onest’uomo”

C. “Di Metello…”

D. “Votate Lucio Ceio Secondo come edile. Procolo e Canto lo chiedono”

E. “[Votate per il duumvirato] Lucio Cecilio Capella”

5 Fragment of painted plaster

Black letters

Julio-Claudian or Flavian age

Pompeii, II 4, 6, north facade of the complex of the praedia of Julia Felix

Inv. 4713

B. “Vote for Aulus Vettius Verus for aedile in charge of streets and sacred and public buildings, a man worthy of public administration and an honest man”

C. “Of Metellus…”

D. “Vote for Lucius Ceius Secondus for aedile. Procolus and Cantus request it”

E. “[Vote for] Lucius Caecilius Capella [for duumvir]”

6 Frammento di intonaco dipinto

Lettere dipinte in nero, in parte svanite

Età flavia

Pompei, VIII 7,16, sulla parete sinistra dell’ingresso 16 del ludus gladiatorius

Inv. 4660

“A Popidio Rufo, invitto organizzatore dei giochi gladiatorii; ai difensori dei coloni, felicemente”

Opera in prestito presso la mostra “Gladiator. Die wahre Geschichte”

Basilea, AMB - 22 settembre 2019 - 22 marzo 2020

6 Fragment of painted plaster

Black letters, partly faded

Flavian age

Pompeii, VIII 7, 16, on the left wall of entrance 16 of the ludus gladiatorius

Inv. 4660

“To Popidius Rufus, unsurpassed organizer of gladiator games, to the protectors of the colonists, with well wishes”.

On loan “Gladiator. Die wahre Geschichte”

Basilea, AMB - 22 settembre 2019 - 22 marzo 2020

7 Graffito con gladiatore

Pompei

Inv. 4697

Opera in prestito presso la mostra “Gladiator. Die wahre Geschichte”

Basilea, AMB - 22 settembre 2019 - 22 marzo 2020

7 Graffito showing a gladiator

Pompeii

Inv. 4697

On loan “Gladiator. Die wahre Geschichte”

Basilea, AMB - 22 settembre 2019 - 22 marzo 2020

8 Frammento di intonaco dipinto

Lettere graffite

Età neroniana (prima del 62 d.C.?)

provenienza sconosciuta

Inv. 4705

Righe 1-3: “(Si è svolto) il primo spettacolo gladiatorio di Marco Mesonio Salluviano nei giorni... e 2 maggio”

Riga 9: “Si e svolto (un secondo) spettacolo gladiatorio nei giorni 11-15 maggio”

Seguono, su due colonne, i nomi di varie coppie gladiatorie combattenti; le coppie sono costituite di Thraeces, gladiatori con armatura tracia; murmillones, gladiatori con elmo sul quale era effigiato un pesce; essedarii, gladiatori che combattono dal cocchio; retiarii, gladiatori armati d’una rete e d’un tridente; hoplomachi (scritto sempre opl-), gladiatori catafratti, armati di tutto punto. Tra i gladiatori combattenti nel secondo spettacolo è ricordato inoltre forse un dimachaerus, gladiatore che combatte con due spade.

Opera in prestito presso la mostra “Gladiator. Die wahre Geschichte”

8 Fragment of painted plaster

Scratched letters

Reign of Nero (before 62 AD?)

Unknown provenance.

Inv. 4705

Lines 1-3: “The first gladiator show of Marcus Mesonius Salluvianus (was held) from... to may 2”

Line 9: “A (second) gladiator show was held from may 11 to May 15”

This text is followed by the names of various gladiator pairs matched against one another, listed in two columns. The pairs include Thraeces, gladiators wearing Thracian armor; murmillones, gladiators wearing helmets on which a fish was depicted; essedarii, gladiators fighting on charriot; retiarii, gladiators armed with a net and trident; hoplomachi (always written without the h), gladiators wearing heavy armour. A dimachaerus, that is, a gladiator fighting with two swords, is possibly mentioned among the fighters in the second show.

On loan “Gladiator. Die wahre Geschichte”

Basilea, AMB - 22 settembre 2019 - 22 marzo 2020

9 Frammento di intonaco dipinto

Lettere dipinte in rosso

Età flavia?

Pompei, sulla facciata tra VII 16, 2 e VII 16, 3 cd. casa di Aemilius Crescens

Inv. 4669

A. “Emilio saluta Cissonio fraternamente”

B. “(Votate) Publio Paquio Procolo ed Aulo Vettio Caprasio Felice [come duoviri], Marco Epidio Sabino e Quinto Mario Rufo [come edili]. Emilio C[elere?]”

9 Fragment of painted plaster

Red letters

Flavian age?

Pompeii, on the facade between VII 16, 2 and VII 16, 3, so-called House of Aemilius Crescens

Inv. 4669

A. “Aemilius fraternally greets Cissonius”

B. “(Vote) for Publius Paquius Procolus and Aulus Vettius Caprasius Felix [for duoviri], Marcus Epidius Sabinus and Quintus Marius Rufus [for aediles]. Aemilius C[eler?]”

10 Frammento di intonaco dipinto

Lettere dipinte in rosso

Pompei, VIII 7, 16 sulla parete destra

Inv. 4663

“Perennino ad Ocella, Ninferote e Icaro, un saluto particolare”

10 Fragment of painted plaster

Red letters

Pompeii, VIII 7, 16, right wall

Inv. 4663

“perenninus to Ocella, Ninferotes and Icarus, a special greeting”

11 Frammento di intonaco dipinto

Lettere graffite

Ercolano. Casa II, 2, colonna angolare del peristilio

Inv. 4698

Lista di nomi, greci e latini, forse di schiavi, per lo più ben noti nell’onomastica romana.

11 Fragment of painted plaster

Scratched letters

Herculaneum, House II, 2, peristyle, corner columns

Inv. 4698

List of Greek and Latin names, possibly of slaves. They are mostly common names in the Roman world.

12 Frammento di intonaco dipinto

Lettere graffite

Pompei: V 1 o V 2

Inv. 4693

“Chi ebbe mai occasione di notare con quanto talento il giovane Sepumio esegue il gioco del serpente, sia tu uno spettatore della scena o abbia passione per i cavalli, possa tenere sempre e ovunque eguali i piatti della bilancia”

12 Fragment of painted plaster

Scratched letters

Pompeii: V 1 o V2

Inv. 4693

“If you ever had the opportunity to remark with how much talent the young Sepumius plays the snake game, whether you are a spectator of the theater or have a passion for horses, may you always keep the pans of the scale in balance, wherever you are”

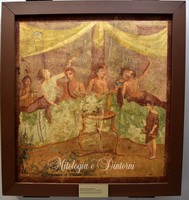

13 Frammento di intonaco dipinto

Circa 50 d.C.

Pompei, V 2, 4 dalla parete ovest del triclinio r

Inv. 120030

Scena di banchetto

13 Fragment of painted plaster

AD 50

Pompeii, V 2, 4, from the west wall of triclinium r

Inv. 120030

Banquet scene

14 Frammento di Intonaco dipinto

Lettere dipinte in bianco

Circa 50 d.C.

Pompei, V 2, 4 dalla parete nord del triclinio r

Inv. 120031

“Divertitevi, e io canto” In corrispondenza dell’ultimo personaggio a destra, si legge: “Così è la vita; sta’ bene”

14 Fragment of painted plaster

AD 50

Pompeii, V2 4 from the north wall of triclinium r

Inv. 120031

“Enjoy yourselves, and I sing”

Next to the last figure on the right, one reads: “That’s how life is; be well”.

15 Frammento di intonaco dipinto

Lettere graffite

Circa 50 d.C.

Pompei, V 2, 4 dalla parete est del triclinio r

Inv. 120029

Nel quadro con la raffigurazione del momento conclusivo di un banchetto sul primo personaggio a sinistra è graffita la parola: “lo so” mentre accanto alla testa di un altro personaggio è graffito “state bene”. Accanto alla testa dello schiavo che avvolge questo personaggio è graffito ISISA(?). Sull’ultimo personaggio a destra ancora sdraiato sul triclinio è graffito “bevo”.

15 Fragment of painted plaster

Scratched letters

Ca. AD 50

Pompei, V 2, 4, from the east wall of triclinium r

Inv. 120029

In the picture showing the final stage of a banquet, above the first figure on the left, is the word “I know”.

Alongside the head of another person is the inscription “be well”. Next to the head of the slave who is swathing this person is the graffito ISISA (?).

On/Above the last person to the right, who is still reclining on the couch, is the graffito “I drink”.

16 Intonaco dipinto

Lettere dipinte

Dopo il 50 d.C.

Pompei, VI 14, 36, Bottega di Salvius, parete nord dell’ambiente a.

Inv. 111482

Serie di vignette con figure di uomini e donne, al di sopra delle quali sono scritte delle frasi che, a partire da e, rappresentano le fasi di un alterco fra giocatori di dadi. Molto nel loro contenuto rimane oscuro.

16 Painted plaster

Painted letters

After AD 50

Pompeii, VI 14, 36, shop of Salvius, north wall of room a

Inv. 111482

A series of vignettes with figures of men and women, above whom are written sentences which, starting from e, represent the stages of a dispute between dice players. Much of their content is still obscure.

17 - 18 - 19 - Forse casa di Giulia - Privi di didascalia

17 - 18 - 19 - Perhaps the home of Julia - With no caption

20 Frammento di intonaco dipinto

Lettere dipinte in bianco

35-50 d.C.

Pompei, IX 6, d-e, dal tablino e, parete est

Inv. s.n.

“Enea”

“Didone”

20 Fragment of painted plaster

White letters

AD 35-50

Pompeii, IX 6, d-e, from tabl. num e, east wall

Inv. No number

“Aeneas”

“Dido”

21 Frammento di intonaco dipinto

Lettere dipinte in bianco

35-50 d.C.

Stabiae

Inv. 9599

“Di Didone”

21 Fragment of painted plaster

White letters

AD 35-50

Stabiae

Inv. 9599

<p<“dido’s”< p="">

22 Frammento di intonaco

Lettere graffite

Dopo il 50 d.C.

Pompei, VI 7, 6 ambiente 13, parete ovest

Inv. 4694

“Effettivamente Venere cattura con la rete (?): poiché insidia il mio consanguineo (?), provocherà tumulto nelle vie; lui si auguri una buona navigazione, ciò che chiede anche la sua Ario”

22 Plaster fragment

Scratched letters

After AD 50

Pompeii, VI 7, 6, room 13, west wall

Inv. 4694

“Truly does Venus catch with her net (?): since she is stalking my next-of-kin (?), she will cause a commotion in the streets; what he should wish for is safe sailing, which is also what his Ario asks for”

23 Frammento di intonaco

Lettere graffite

Pompei, VI 14, 43, atrio 2

Inv. 4665

A. “Una bionda m’ha insegnato a odiare le more. Le odierò se mi sarà possibile; se no, le amerò, anche contro voglia. Scrisse la Venere fisica pompeiana”

B. Pothus

C. Crocum Primus

23 Plaster fragment

Scratched letters

Pompeii, VI 14, 43, atrium 2

Inv. 4665

A. “A blonde woman taught me to hate black-haired women. I will hate them if I can; if not, I will love them, even against my will. Thus wrote the Pompeian Venus physica”

B. Pothus

C. Crocum Primus

24 Frammento di intonaco

Lettere graffite

Pompei, VI 14, 43, accanto all’ingresso della casa

Inv.4685

“Qui e ora ho scopato una ragazza bella d’aspetto, da molti lodata, ma dentro era soltanto fango”

24 Plaster fragment

Scratched letters

Pompei, VI 14, 43, next to the main entrance of the house

Inv. 4685

“Here and now I copulated with a girl who is beautiful to look at and praised by many, but inside she was nothing but filth”

25 Il dossier sulla concessione della civitas romana al liberto ercolanese Lucio Venidio Ennico

Trittico di tavolette lignee cerate e carbonizzate, parzialmente ricomposto da innumerevoli frammenti.

Ercolano, Casa del Salone Nero, VI, 13 e 11, 1939, 22 marzo 62 d. C.

Il trittico è l’atto conclusivo della procedura seguita dal liberto ercolanese L. Venidius Ennychus, per ottenere la cittadinanza romana, per sé, per la moglie Livia Acte e per la sua figlioletta di un anno. Ennychus appartiene alla categoria giuridica dei Latini Iuniani, e, come tale possedeva, al pari dei liberti cittadini, i tria nomina e il ius commercii, cioè poteva agire nel mondo degli affari, ma non poteva né ricevere né trasmettere beni per testamento, né lasciarli ab intestato ai discendenti; non aveva neppure la patria potestas sui figli. Alla sua morte i suoi beni sarebbero andati al suo patrono o eredi e in loro mancanza all’erario.

Nel 69 Ennychus, ormai più che cinquantenne, era ancora in attività; in seguito non si sa più nulla di lui. Si è supposto che egli fosse il proprietario della casa del Salone Nero, una delle più grandi e importanti di Ercolano, perché sul ballatoio della domus fu rinvenuto il suo archivio; dagli atti che questo conserva si evince che fosse un mercante - negotiator, dedito anche a piccole operazioni finanziarie.

25 The dossier on the concession of civitas romana to the Herculanean freedman Lucius Venidius Ennychus

A triptych of waxed and carbonized wooden tablets, partially reconstructed from innumerable fragments Herculaneum, House of the Black Hall, VI, 13 and 11, 1939, March 22, AD 62. This triptych records the final act in the legal procedure the Herculanean freedman L. Venidius Ennychus undertook to obtain Roman citizenship for himself, his wife Livia Acte, and his one-year-old daughter. Ennychus belongs to the juridical category of Latini Iuniani. As such, like urban freedmen, he bore the tria nomina and had ius commercii, that is, he was entitled to operate in the business world; however, he could neither receive nor hand down property by testament, nor bequeath property ab intestato to his descendants. Neither did he have patria potestas over his children. On his death, his property would have gone to his patron or heirs or, in lack thereof, to the state treasury.

In 69 AD, Ennychus, by then past his fiftieth year, was still active. We have no information about him thereafter. Some have suggested that he owned the House of the Black Hall, one of the largest and most important in Herculaneum, because his archive was found here, on an upper floor. The records preserved in this archive indicate that he was a negotiator, a merchant, who also engaged in minor financial operations.

26 Diploma militare di Nerva Desidiato figlio di Laido

Bronzo

7 marzo 70 d.C.

Ercolano

Inv. 3725 (CIL X 1402; CIL XVI 11)

“L’Imperatore Vespasiano Cesare Augusto, rivestito delle potestà di tribuno della plebe per la seconda volta, console per la seconda volta /ai veterani che hanno militato nella seconda legione/ Adiutrix Pia Fidelis, che hanno percepito venti o più stipendi annuali/e sono stati congedati con onore/i cui nomi sono scritti sotto/agli stessi figli e ai loro discendenti/ ha dato la cittadinanza e il diritto di matrimonio (secondo il rito e il diritto romani) con la moglie che avevano al momento della concessione della cittadinanza, o, se erano celibi/con le mogli sposate successivamente /per un massimo di una sola moglie per ciascun veterano”

Tav. II int. col. 3; Tav. I est. col 1

“Nel giorno delle None di Marzo (7 marzo); consoli l’Imperatore Vespasiano Cesare Augusto per la seconda volta, e Cesare Vespasiano figlio di Augusto”

Tavola 1 col. 5 pos. 46.

“(Diploma) di Nerva Desidiato figlio di Laido/Trascritto e riscontrato dalla tavola di bronzo affissa a Roma, sul Campidoglio, nel podio dell’ara della famiglia Giulia, lato destro, di fronte alla statua del Padre Libero”

Tav. Il est. col.4 Seguono i nomi di sette testimoni.

L’intestatario del documento è Nerva Desidiato, un veterano della legione II Adiutrix Pia Fidelis. Il diploma consta di due tavolette di bronzo che erano chiuse e sigillate insieme, con lo stesso testo riprodotto due volte, sulle facce sia esterne che interne. La prima faccia esterna riporta il dispositivo e la posizione dell’originale di cui il diploma è copia; la seconda, i nomi dei testimoni. Il documento è datato al 70 a.C. dalla coppia consolare composta dall’imperatore Vespasiano, nell’esercizio della seconda potestà tribunizia, e dal figlio Tito.

I diplomi militari erano attestati di congedo con onore rilasciati ai legionari che erano cittadini romani, o, come in questo caso, di concessione della cittadinanza romana e del diritto di matrimonio (conubium) a soldati di estrazione provinciale arruolati in corpi ausiliari o nella flotta e congedati dopo una ferma di 20-25 anni. Gli originali di questi dispositivi erano custoditi a Roma.

26 Military diploma of Nerva Desidiatus, son of Laidus

Bronze

March 7, 70 AD.

Herculaneum

Inv. 3725 (CIL X 1402; CIL XVI 11)

“The emperor Vespasian Caesar Augustus, holding the power of tribune of the plebs for the second time, consul for the second time/to the veterans who served in the second legion/ Adiutrix Pia Fidelis, who have received twenty or more annual wages/and have been honorably discharged/whose names are written below/and to their children and descendants themselves/l have given citizenship and the right to marry (according to Roman rite and law) with the wife they had at the time they were granted citizenship, or, if they were unmarried/with the wives married subsequently/for a maximum of one wife for each veteran”

Tablet 2, inside, column 3; Tablet 1, outside, column 1

“In the day of the nones of March (7 March),under the consulate of the emperor Vespasian Caesar Augustus, consul for the second time, and Caesar Vespasian, son of Augustus”

Table 1, column 5 pos. 46.

“(Diploma) of Nerva Desidiatus son of Laidus/ Transcribed on and testified by a bronze tablet affixed in Rome on Capitol Hill, on the podium of the altar of the Julia family, right side, in front of the statue of Father Liber”

Tablet 2, outside, column 4. The names of seven witnesses follow.

The document is in the name of Nerva Desidiatus, a veteran of the second legion, Adiutrix Pia Fidelis. The diploma consists of two bronze tablets, which had been placed face to face and sealed together, each carrying the same text reproduced twice, both on the outside and on the inside. The first outer side indicates the name of the holder and the place where the original this diploma is a copy of is exhibited. The second outer side lists the names of the witnesses. The consular pair constituted by Vespasian holding the power of a tribune for the second times and his son Titus yields the date of AD 70.

Military diplomas were honorable discharge certificates that were either issued to legionaries who were already Roman citizens or, as in this case, granted citizenship and the right to marry (conubium) to soldiers from the provinces enlisted in auxiliary corps or the navy and discharged after serving for 20-25 years. The originals of these certificates were kept in Rome.

Fotografie di Giorgio Manusakis